The massacre of 22,000 men in the Katyń atrocity is difficult to comprehend without relating it to the personal. The story of Bogusław Piesiewicz, who suffered a double tragedy in April 1940 as a child, is a harrowing one. In my youth I knew him through my parents in Leeds, a very literate, passionate man, who strove for justice until his dying day… this is his story, translated into English.

My father Staś

My father, Słanisław Piesiewicz, was born in Maciejowice in September 1892. In 1914 he was drafted into the Russian army and took part in the Russian-German war. Together with several other Poles, they “disappeared” and after many adventures, Father found himself in Tashkent, and then in Mumbai, India. After returning to Poland from Mumbai, my father settled in a nice district in the town of Zdołbunów in Wołyń (near Równe), where next to the train station was the end of the wide Soviet track and a hub station.

Zdołbunów now: Lyoha123 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

My father, as an employee of PKP (Polish railways), earned good money in the Kresy (borderlands) region. Being fluent in spoken and written Russian, he would also work with other railwaymen across the Soviet border, for which they got extra rations of food. Father told me that at the station in Szepietowce, they were allowed to get out of the train to their shed, and when they threw leftovers behind the hut, Ukrainian children would fight each other for the scraps. These were times of famine in Ukraine…

Every few days, a Soviet passenger train came to the station in Zdołbunów: often a powerful “Ordzhonikidze” type locomotive with a howling, piercing whistle and a set of 5 or 6 impressive carriages (all for show). Sometimes they converted the carriages to the normal European gauge or the passengers moved to Polish ‘Pullmans’ and after a few hours they would leave, for example to Berlin. A few times Father took me with him, wanting to show me the Soviet train. I would stand at a distance, as Father greeted the Soviet train manager. They would talk for quite some time, Father would sign some documents (there were several policemen and undercover officers around), and then we would drive home.

Ordzhonikidze train: Valentina Zvyagina

The day it began

On September 17, 1939, the Soviets entered Poland. By the afternoon they were already in Zdołbunów. We listened on an old radio transmitter, to the then commissar of foreign affairs Vyacheslav Molotov-vel-Skrjabin – “It was enough to strongly attack the German army, and invade with our Red Army for nothing to be left of the Versailles Treaty.” My father cried and said – “Poland is no longer”. In the evening of that day, I saw through the crack of the kitchen door as Father and Mother spread a lot of” Mikołajewki “on the table – gold five and ten rouble coins that they had brought back from Tashkent, where Father, as the right hand man of Mr. F. Goetel, ran a supply office for the Russian Army.

After dividing the gold rubles, I saw Father at night carrying something quite long, wrapped in oilcloth which he buried in our large garden. Much later I learned from Mother that it was Father’s service revolver, because my father had worked with the counterintelligence section of the so-called “Dwójka” and had contacts with certain Soviet citizens. On the next day, September 18th, my father went by bicycle to the station to find out whether he should continue working. We waited almost until midnight, but for nothing. My father did not come back. A railwayman friend lightly knocked on the window and my mother let him. He announced to us that “Staś (my Father) had been arrested by the NKVD along with several other railwaymen, including the station’s administrator, former lieutenant of the reserve, Mr. Strzałka, and had been taken to the prison in so called “Górki” in the nearby large city of Równe (12 km from Zdołbunów). He then silently left our house.

Visits to Równe

Railwaymen friends often took me to Równe with food packages for my father. The NKVD accepted them, but they never said if my Father was there. Sometimes I walked around the prison hoping that maybe I would see something or ask someone (there was a wide prison gate behind which lay heaps of coal and sometimes several prisoners were transporting coal from there with wheelbarrows). In vain. Somewhere around Christmas 1939, Dr. Sobański the railway doctor was released from the prison, Father’s friend and partner in the card game preferans (like whist). He turned up at our house secretly at night, and I listened at the door. I remember when he said: “Kaziu, Staszek was beaten so badly he tried to take his life.” After a few weeks, they arrested Dr. Sobański again and temporarily left him in Zdołbunów under the control of the so-called “Magistrate”, because there was no prison in Zdołbunów. That night, the doctor hanged himself in the toilet because he knew what was going to happen to him.

Bolshevik ramp

On April 4, 1940, news spread in Zdołbunów that on the so-called “Bolshevik ramp”, the area where the wide Soviet train tracks met the local ones, there was a freight train with prisoners from Równe and other cities. I picked up Father’s bike from the railwayman’s cabin: surprisingly, it had not been commandeered, and drove to this ramp.

Zdołbunów: Yaroslav F (CC BY-NC 2.0)

There were about ten cattle wagons there. The area was busy with NKVD men and militia, but prisoners looked out of the window bars. I remember there were women in one carriage – as it turned out, they were harcerki (girl scouts) singing the song “Rota” by Konopnicka. The Soviet guards were pounding the wagon with rage with the butts of their rifles, cursing vulgarly just as the Soviets could, however, ignoring the frequent kicks from NKVD men and militiamen, I kept shouting my father’s name towards the barred windows. In the end, someone shouted back, “son go to the last wagon, your father is there.” I ran in that direction, receiving a few more pushes and curses on the way, and finally I stood a dozen steps away from the half-open door, where the guard was giving out “kipiatok” (hot water) and some scraps. One of the NKVD men shouted at me to “leave” because “we will shut you up as well”. Suddenly, from one of the open doors, one of the prisoners shouted loudly in Russian: “You scum, will you not let a son say goodbye to his father for the last time?” Evidently something human spoke to the Bolshevik’s soul because he took my arm and said, “Come here boy, talk to your father, hurry, hurry.”

Never see each other again

Second in the line, with a mess tin, stood my Father. In a desperate voice he said, “My son, we will never see each other again, they are taking us to the main interrogation place – I think – to Charków. I am very cold (he was without a coat), try and bring me my sheepskin, tomorrow morning: we will be here until 9 o’clock. Do not say anything to my mother until tomorrow.”

Tearfully I went home. I tried not to let it be known that anything was wrong. In the morning, under some pretext, I got on the bike (on the frame because I could not reach the pedals from the saddle) and with the sheepskin coat wrapped in string I rushed to the “Bolshevik” ramp. I threw the bike between the rails and looked terrified as the train began to slowly move away – more than an hour earlier than Father had told me to come, when they were to give them food again. I ran after the train shouting: “Daddy, Daddy”, weeping fervent tears, as the train slowly moved away, further away … I saw from the last wagon in which my father was, someone waving a bright rag through the barred window – it had to be my father, he had managed to see his son running after the train, through the gaps. Heartbroken, I returned home.

Russian tracks: Bernt Rosad (CC BY 2.0)

They came for Mother and me

When they came for Mother and me on April 13, 1940, the oldest NKVD man read the official announcement: “Kazimiera Pietrowna Piesiewicz nie biespakojties, jedietie k’waszemu mużu, on rabotajet po swojej specjalnosti na Pietropawłowskiej żieleznej dorogie.” (Kazimiera Pietrowna Piesiewicz, do not worry, you are going to join your husband, he’s working in his speciality on the Pietropawłowsk railway). They lied shamelessly so as not to panic people and provoke shouts of despair.

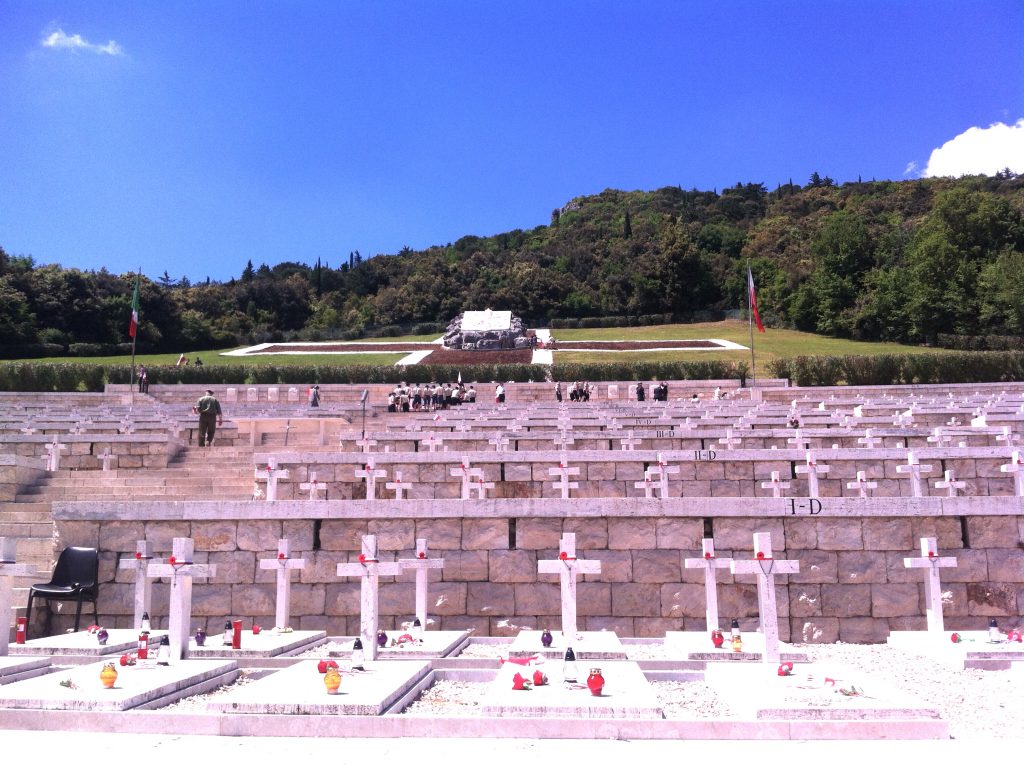

After that, for me there was northern Kazakhstan, the so-called “amnesty”, joining the Junacy (cadets), where I spent a year. As a radio-telegraphist with 30 or 40 others, I was assigned to the 9th company of Signals of the 2nd (then) Armoured Brigade of General Bronisław Rakowski (later, in the spring of 1945 renamed at the 2nd Warsaw Armoured Division). As probably the youngest soldier of the II- Corps of Gen. W. Anders, I took part (though not directly) in the battle of Monte Cassino. I was 16 years and several months old.

The quest for truth

The quest for truth

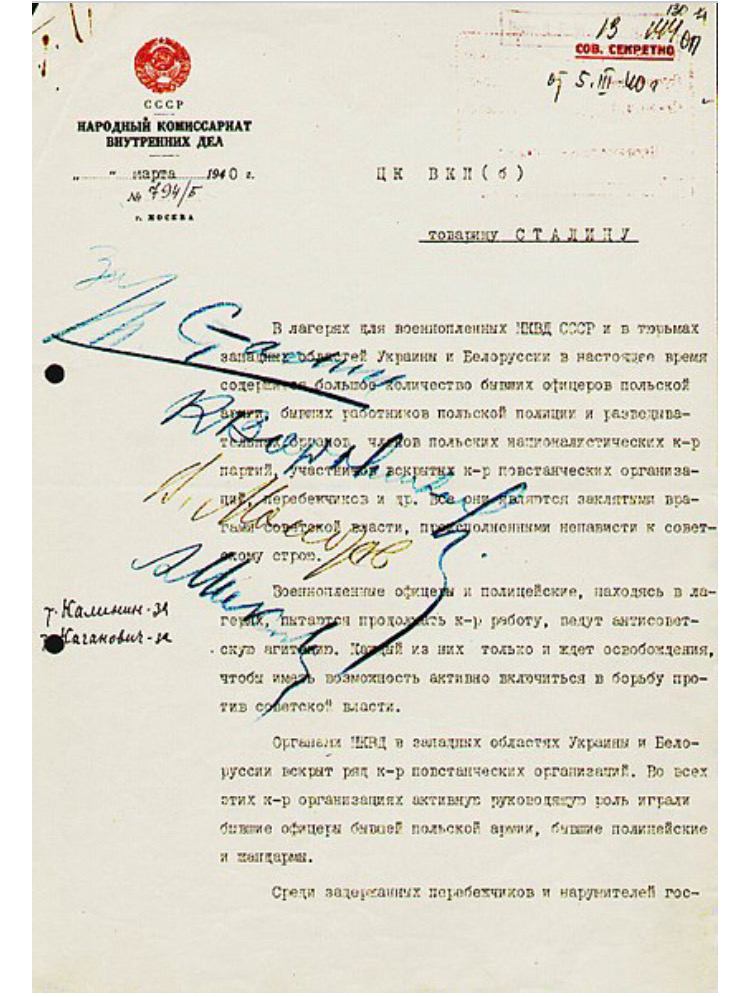

From time to time I wrote to many places, including the Red Cross in England, to the late Professor Zdzisław Stahl, wanting to find out where my father had died, because of that I had no doubt. I also corresponded with the prosecutor Aleksander Herzog, then advisor to the Minister of Justice in 1994-1996. At his request, the Dziennik Polski published his very long letter to me on April 26, 1995, including his appeal to send to the address of the Ministry of Justice, the names of those arrested in Belarus, to establish a possible place where they were murdered. The Prosecutor A. Herzog invited me to visit him in the ministry’s office, which I did in June 1995. I found out that my father Stanisław appears on the so-called “Ukrainian List”, as murdered in April 1940. According to the NKVD list, 3435 Polish citizens were shot in Ukraine, about 7,500 executed in Belarus and, above all, 14,700 Polish prisoners of war, were all executed [at Katyń and surrounding areas] on the basis of the same order, the Political Bureau of the Soviet Union (b) USSR order of March 5, 1940.

I have two books in which there are exact lists with surnames and an NKVD code on the basis of which it can be calculated on which day in April or a little later, Polish citizens were murdered in Ukraine in 1940.

Acknowledgement

This is the story of Bogusław Piesiewicz’s early life. As some of my mother’s family lived in Zdołbunów during the

war, his story is especially poignant to me.

On April 13, 1943, the Germans announced that they had discovered mass graves of Polish officers in the Katyń forest near Smolensk, in western Russia. The murder of 22,000 of Poland’s officers and administrative class was not officially acknowledged by the Russians as having been ordered by Stalin until 2010 (having released the first documents in the 1990s ). The USA and UK had evidence of the massacre since the discovery, but suppressed it until the late 1990s, when archived reports were published, recognising the concern of the Polish people that it had never been acknowledged sufficiently internationally (FCO 1996).

Bogusław and thousands of other children, wives and parents suffered further, deported to the depths of Kazakhstan for forced labour, their agony endured for all of these years. 13 April every year means so much more than the discovery of another war crime. Some, like Bogusław, continued to press the authorities for answers, fervently righting slurs on his country and promoting the truths known for so long, yet not acknowledged. He arranged for an urn of soil from Katyń to be set in the wall of Leeds Polish Church with a memorial plaque, one of many in towns and cities around the world around which Poles gather to remember throughout April.

Translated from an article in Panorama magazine, published in Nottingham by M. Polkowska

If you would like to read more on this subject:

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2