The beautiful panorama of the city of Wilno has been an inspiration for artists and writers throughout the centuries who called it home. Adam Mickiewicz to Juliusz Słowacki, Stanisław Moniuszko to Czesław Miłosz. A Kraków exhibition* this summer features many depictions of the city as well as a new perspective of the interwar period in the newly formed II Polish Republic.

Art of reminiscence and of modernism

“Of all Polish cities, Vinius had ‘the least materialistic culture and always cared little for it, nurturing high values of the spirit”

(Witold Bunikiewicz ‘Tryumf Wileńczyków w sztuce’ Świat 1933, no.8 p.12)

Although as a former outpost of the Russian Empire Wilno was poor economically, artists focused on its picturesque nature, set amongst wooded hills and with a rich history of architecture. Wilno’s greatest strength was its cultural life with the revived Stefan Batory university being one of only three in Poland teaching visual arts.

The Wileńskie Towarzystwo Artystów Plastyków (Wilno Society of Artists) was founded in 1920 organising exhibitions all over Poland. Ludomir Śledziński was its most prominent character but also Bronisław Jamontt, Michał Rouba and Tymon Niesiołowski amongst others were in the first league of Polish artists. Graphic art was also highly developed with Jerzy Hoppen’s very popular sketches of Vilnius architecture.

A more contemporary city is found in the world of Rouba’s many paintings showing the ‘melancholic calm of its existence’ (Dariusz Konstantynów).

“The domes of the Russian church are golden in the distance, three stone crosses on the highest hill, the Wilia flowing not so slowly, located in the middle of a gordian knot of hills, this is how the seasons pass in the restless sky” (Giorgio Ruggeri).

Jan Bułhak has become famous for his images of Wilno at this time, photographed to document the monuments of the region to enhance patriotic feeling. He chose subjects and techniques to emphasise the painterly qualities of his work and was successful in including photography in exhibitions of the time.

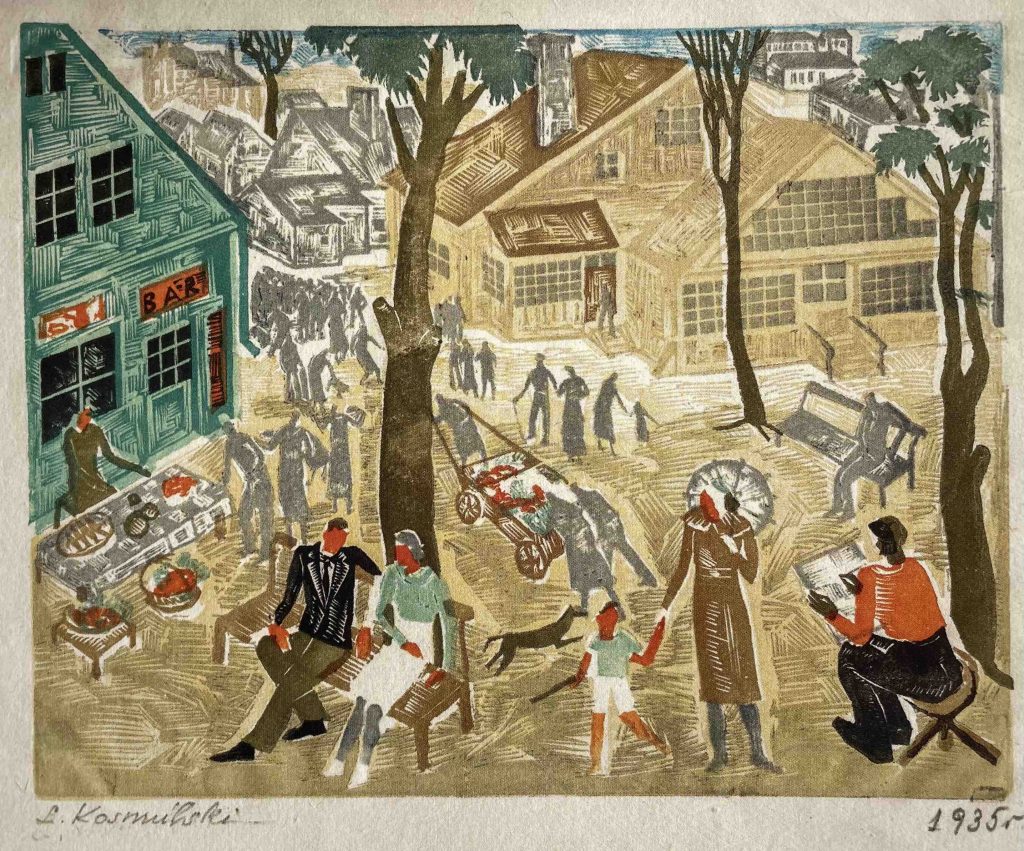

Young artists painted everyday life in streets but few represented the poverty or social inequality of the times. Overall the artists encompassed a new classicism, popular after World War I but also the colourist movement and neorealism, harking back to a romantic past but also showing an urban idyll.

A history of struggles

“the Poland we call pre-war today was p o s t – war Poland for its residents. Social memory was shaped by the experiences of the recent world and its Polish-Bolshevik wars, uprisings and border struggles…… Military metaphors and images were also readily used to describe Vilnius; a rampart, a fortress, a post, a bastion. (Grzegorz Piątek)

Wilno was Marshall Józef Piłsudski’s place of birth and he fought for the city in April 1919 as part of the Polish-Bolshevik war but the Soviets re-entered in July 1920 giving the city to the Lithuanian army who had fought against the Poles. Piłsudski summoned General Żeligowski to take Wilno by force and his troops entering on 9 October declaring it the Capital of a separate state of Central Lithuania, just before peace was declared between the Poles and Soviets.

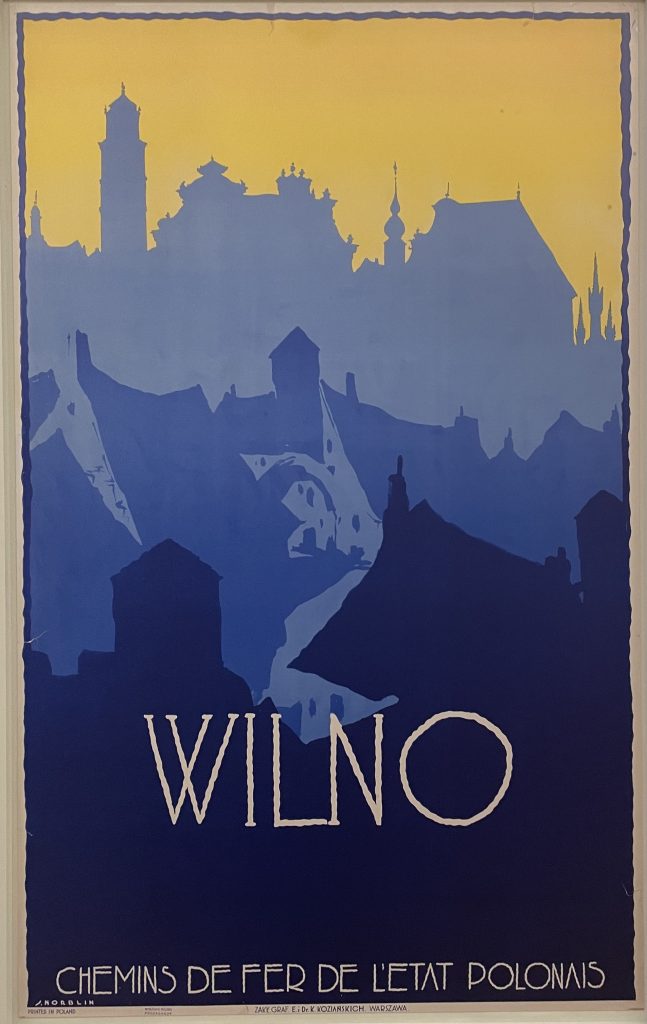

Free elections in 1922 annexed this new state to Poland but Poland and the new state of Lithuania did not resume political relations until 1938. Art became an important tool in the fight for affiliating the city to the Polish state, reminding Poles with publications of national architecture including the well known religious icon at Ostra Brama (Gates of Dawn painting of the Virgin Mary) that its culture lay in Wilno. Colourful posters also began inviting tourists to the city, reached by “Latający Wilnianin” high speed train from Warszawa in six and a half hours.

But it must have seemed a fairly settled town by the time my great-grandmother moved there in 1930 and settled my grandmother into school. Despite needing modernisation “Weary and sleepy facades of the baroque architecture, rusty gates, the rumbling cobblestones.” Giorgio Ruggeri.

A multicultural city

A film attached to the exhibition made by Italian Giorgio Ruggeri, invites Lithuanians, Jews and Poles to give their opinion on who Wilno belongs to, what is its culture. In 1931 Wilno had a population of 65.9% Poles, 28% Jews, 3.8 Russians and 0.8 Lithuanians in contrast to 34 years earlier when the proportion of Poles and Jews was fairly similar.

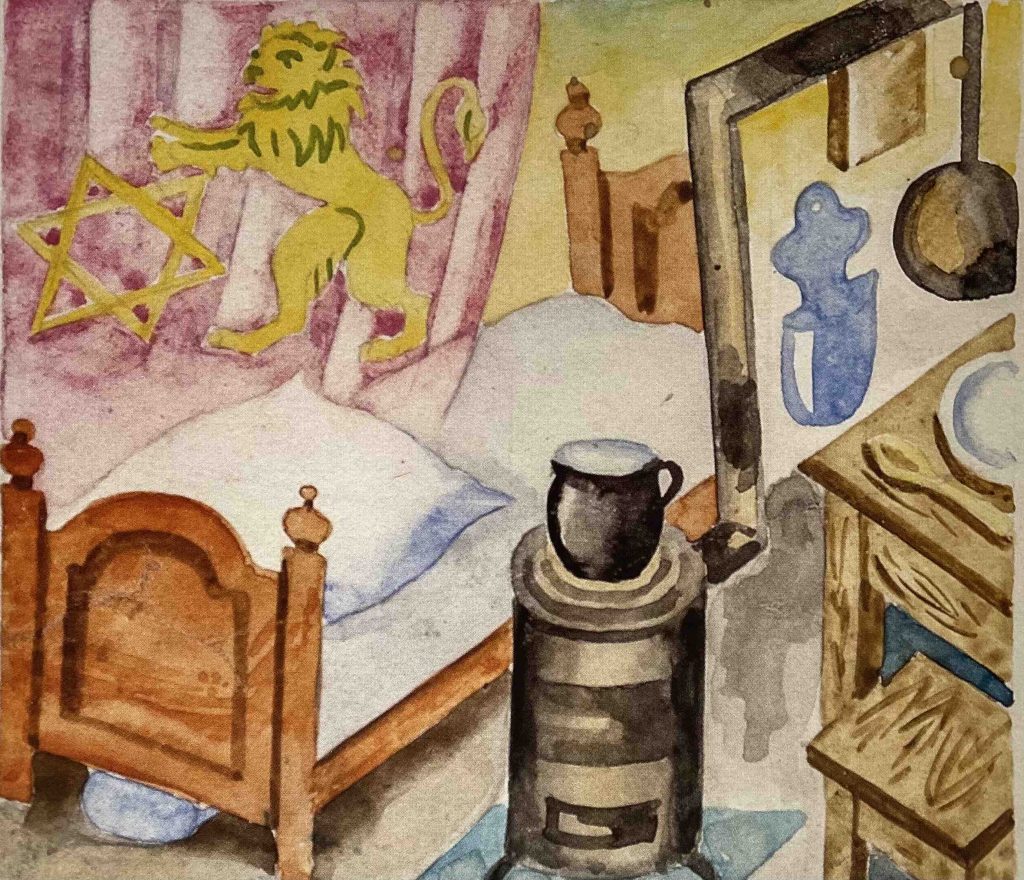

A Jew’s room, Bencjon Michtom 1934

The film presents a uneasy tension between the different nationalities which inevitably increased throughout the 1930s as Europe headed towards another dark period. Jewish artists had their own Union of Jewish artists but did take part in some joint exhibitions with the Polish artists. Much of the work of this period carries a great deal of symbolism.

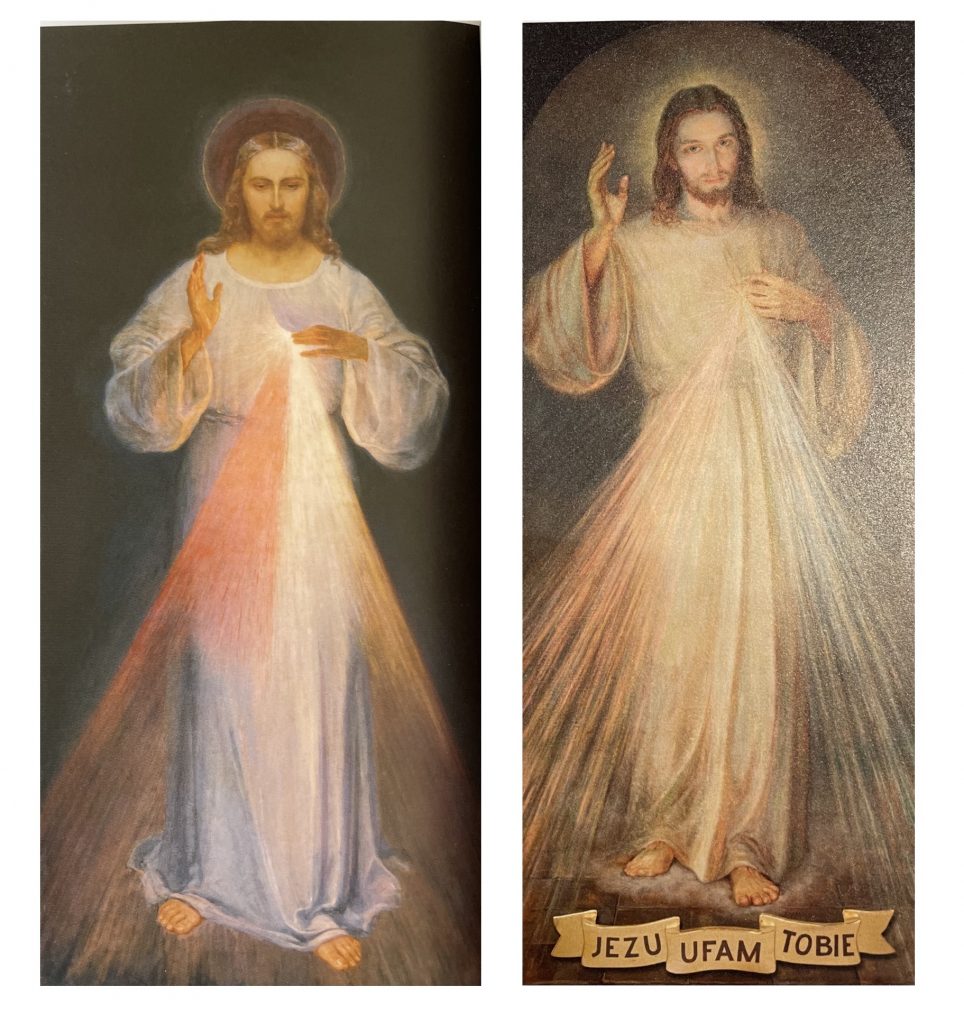

A tale of two religious works of art

Eugeniusz Kazimirowski unwittingly created an outright masterpiece of religious art. Asked in 1934 to paint the vision of the Divine Mercy of Jesus as seen by Sister Faustina Kowalska, it did not initially enjoy great popularity in its home in St Michael’s church. The communists shut the church after the war and the picture was taken into hiding.

Meanwhile, a different version was painted by Alfred Hyła in Poland in 1944 and became world famous, now in Łagiewniki, Kraków. Indeed many people think this is the original painting. Even after Lithuanian independence the picture wasn’t at first popular (I saw it for the first time in the Church of the Holy Spirit in 1992), but after restoration, it is now widely venerated again, in its own Sanctuary.

Wilno of our shared memories

My grandmother’s diaries of the time describe “our house in a narrow street covered with grass and a worn path. So I have a village and a city, silence and bustle, though Wilno gives the impression of a quiet town” This echoes Giorgio Ruggeri’s view of ” its spacious stillness, unsymmetrical squares and vast grassy spaces smelling of untouched nature and abandoned gardens”.

This is the Wilno of my grandparents’ time, a city loved by all who inhabited it, yet meaning different things to different people, those who had migrated there and those whose roots were firmly in its soil.

Unfortunately the Second World War more than anything in the previous centuries, wiped out its multiculturalism and transformed Wilno into the Lithuanian city it is today. The most active artists of this unique period left with the Polish refugees, some settling in Toruń but most were scattered and had to find their place in the new reality.

*The exhibition Wilno, Vilnius, Vilne 1918 – 1848. One city – many stories runs until 3 September 2023

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2