On 17 September 2021, to commemorate the day in 1939 when the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, a Museum opened telling the history of Poles deported to Russia since the 16th century. Many years in the planning, it’s located in a pre-war military warehouse. As it was sited next to a train station, its walls will have heard the cries of men, women and children deported by not only the Soviets to Siberia and beyond but also by the Germans to Treblinka.

Deportations for Poles are nothing new especially in the eastern borderlands. The museum covers the exile of soldiers and residents near the border during the Polish-Muscovite wars to Uprisings in the 19th century and finally those in the 1940’s during World War II. Split into three areas, each surrounds the visitor with visual and aural stimuli to imagine how exile would have felt.

The life left behind

Photo from Muzeum Pamięci Sybiru

How many houses in 1940 in the eastern Kresy lands were left empty with last night’s dishes still to be washed up, toys to tidy, clothes hanging up to dry, beds unmade as the inhabitants were taken from them at gunpoint? Certainly several hundred thousand as it is estimated that over a million people were deported.

I’ve written before about which objects in our own houses we would take. Would we have precious family photographs to take with us? Many people were in such a panic they took useless things, their best silver instead of food, though any possession was better than none as it could be sold for food.

“it is the heroes of those times who lead us though the exhibition, this being our tribute to all exiles”

Tadeusz Truskolaski, President of Białystok.

Siberia

“forget your past life (..) don’t think you’ll ever return to your country.”

The Long Bridge – Urszula Muskus

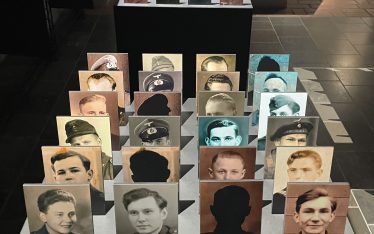

White, empty spaces symbolise the snow, the freezing temperatures and endless flat landscapes which the deportees encountered on being freed from the two or three week journeys by cattle truck or sleigh. Whether Siberia or the empty steppes of Kazakhstan the experiences of countless Poles over the centuries are featured, most poignantly by the portraits of Siberians from all over the world who survived this ordeal, their children and grandchildren. This is the story of peasants, scientists, writers, revolutionaries and ordinary Poles whose crime was to be Polish or simply live in the wrong place.

Katyń

Polish soldiers in Soviet captivity:public domain

“Since dawn, the day began strangely (..) They’ve taken us somewhere into a wood (..) I was relieved of my watch (..) They asked me about my wedding ring, which…Roubles, belt and pocket knife taken away…”

Last diary entry of Major Adam Solski on 9.4. 1940 – Surviving Katyń by Jane Rogoyska

Downstairs in a dark room covered with rusty sheets of metal the focus is on the silhouette of a kneeling soldier. The buttons of officers’ uniforms recovered from the mass graves and the names of all known officers murdered forms the main memorial to the 22,000 plus Polish officers taken prisoner and then shot by the Soviets in the spring of 1940 in a planned extermination of males of the Polish middle classes. Visitors are encouraged to reflect on what humanity is capable of.

Outside a forest of steel poles has grown, full of symbolism depending on how the visitor interprets them. Is it the lost people thrown out of carriages on the way to Soviet work camps, those who lie forever in a foreign land or is it the icy Siberian landscape?

I hope to visit the museum soon and that it does convey the full story of our parents and grandparents with integrity. Please write to me about your experience if you visit before I do. The information about the exhibits was taken from the Museum website and other sources.

You may wish to read:

From the Katyń massacre to Monte Cassino – one boy’s tragic loss

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2