For years few spoke about it. Many shared the feeling “they wouldn’t understand or would laugh so you just closed yourself up.” The story of the horrifying crime carried out by the Russians on the people of Eastern Poland wasn’t well known and still isn’t. How can the forced deportation of up to 1.7 million men, women and children of whom only a third survived, not be common knowledge? The film Forgotten Odyssey tells this story..

As children of those who survived, we too felt the fear of telling other children. When answering how our parents got to the UK, we received incredulous or blank looks as if we were making it up. Now there are books written by the survivors or their children so that this story can be shared. And yet it’s rarely in the public consciousness, despite there being ever more interest in the Second World War.

A documentary film that has been shown in many other countries but should be shown again and again is A Forgotten Odyssey – The Untold Story of 1,700,000 Poles Deported to Siberia in 1940. Made in 2000, I don’t know much about the authors Jagna Wright and Aneta Naszyńska, but both died tragically early. Jagna devoted the last 15 years of her life, cut short by breast cancer, to make two documentary films with professional editor Aneta. Jagna taught herself the craft of filmmaking and started recording the testimonies of the dwindling witnesses to the Siberian genocide. It’s available on YouTube, split into parts – choose the part you know least about to watch or share with friends so they understand. It holds much archive footage, photographs and interviews demonstrating how bleak the political situation was for Poles, even those released.

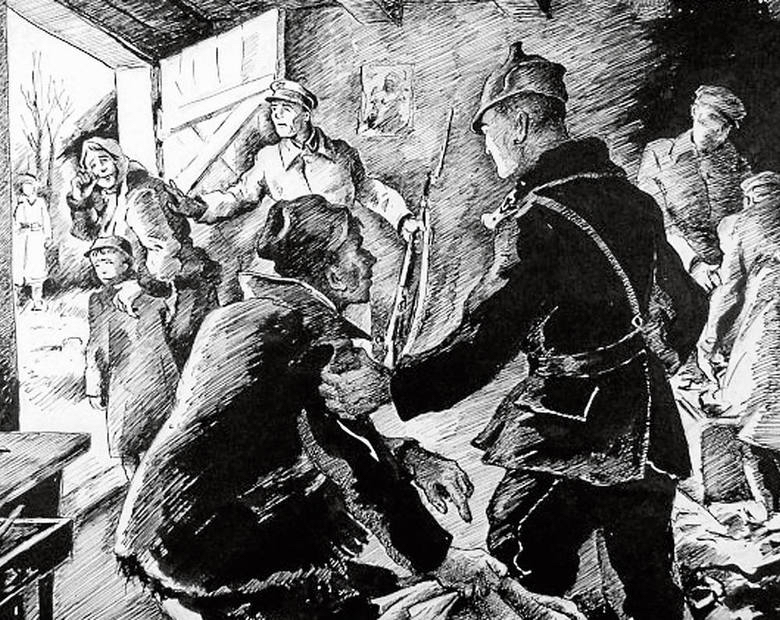

Fear of the unknown

As many of you know, the nightmare began in the middle of the night on 10 February 1940 for many families, including mine and over the following months for others. After Russia invaded Poland, Stalin deported up to 1.7 million Poles to slave labour camps in Siberia, Kazakhstan and the Arkhangelsk Oblast in the north, in cattle trucks. Journeys that lasted weeks until they reached camps where the Russians assured them that bourgeois Poland was finished, and that they would never leave the forests where they had arrived to work with little food or shelter. Each family’s story is unique, seconds or minutes to pack affecting whether they lived or died, as provisions, warm clothes and bedding were vital to survival.

You will die here

The terrible ordeal of working in mines, farms or remote logging camps was often too much for the old or young. If you didn’t work you didn’t eat. The winter temperatures went down to minus 40 yet work carried on. Some splashed themselves with water, which formed an icy armour on their coats to keep warm. No medical attention meant many people died. They were told “you will get used to it and if you don’t you will die the death of a dog”. Food supplies were barely enough to survive on yet the work was incredibly hard. Remember, these are the survivors talking.

Released but where to?

On 22nd June 1941 Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, forcing them to acknowledge all the help they could get to retaliate. In London the Polish Government in Exile and the Soviet Union came to an agreement that the Soviets would release their Polish prisoners so that an army, commanded by General Wladyslaw Anders (also to be set free from prison), could be formed in Russia. The Poles had to find their way across vast distances, helped only by Polish consular officials and Persons of Trust at railway junctions and cities. Some groups numbered less than 10% of the total numbers of prisoners who had entered those camps. The others were long buried under the Siberian snow. And typhus and other diseases killed off even more of the weakened, bedraggled people.

To freedom

In December 1941 as the German armies marched towards Moscow, General Sikorski (the Polish PM in exile) met with Stalin to move the fledgling army to the south of Russia. As the exhausted refugees arrived, General Anders wondered where all the Polish officers were. A further meeting in March 1942 led to agreement that half the army could move to the British zone in Persia (Iran) followed by the other half in July 1942, when Churchill intervened. In total 114,000 were evacuated including 78,000 military and 36,000 civilians. But where were the rest? The German discovery of the horrific Katyń massacres answered that question.

Fighting for a free Poland and homes to return to…

Any Poles still left in Russia and hoping to join the army, were sent back to Soviet farms to work and after the war, some made it back to Poland. Meanwhile the newly formed Polish army fought valiantly alongside the Allies in France, Belgium, Holland and Italy with more than 45,000 losing their lives. The newly proposed borders drawn for post war Poland between Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at Yalta meant all these people had lost their home towns to the Soviets and had no homes to fight for anymore. Letters from Polish soldiers complaining about this, were censored by the British, as the Soviet Union was an official ally and nothing was to be said against them. After the war, the odyssey continued as Poles, refusing to go back to the same regime, were scattered all over the world, wherever they could build a new life.

In the introduction to the film, Norman Davies, the well known historian, recounts that in no British document has this been acknowledged as a war crime and although the recording was made in 2000, I doubt anything has changed. A journalist has commented that “the Poles deported by order of Stalin to Russia, were then deported from history by Western historians”. Watch the film and others like it and share. It means that one more person knows the full truth. Jagna and Aneta also made a second film, a three-part documentary, The Other Truth about the complex history of Polish-Jewish relations.

These women were true pioneers in the film industry, as still very few films are made by women alone. We should not only remember the legacy of these women, we should know it by heart.

Feature image is taken from www.swoopingeagle.com

NB: Numbers of deported Poles continue to be debated. The Institute of National Remembrance most recently (2025) quote much lower figures, based on data in Russian archives, yet historians Roger Moorhouse and Norman Davies argue for at least one million.

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2