Many people say that it would be impossible to establish an independent Polish state in 1918 without the sacrifices made during the Powstanie Styczniowe (January Uprising)of 1863. Józef Piłsudski, like many brought up by Powstańcy (Insurgent) parents, used the Uprising’s tactics to fight for independence 50 years later. In the newly independent Poland, not forgetting the insurgents, he granted these veterans full military rights and the right to military honours for their deeds.

Largest Uprising ever

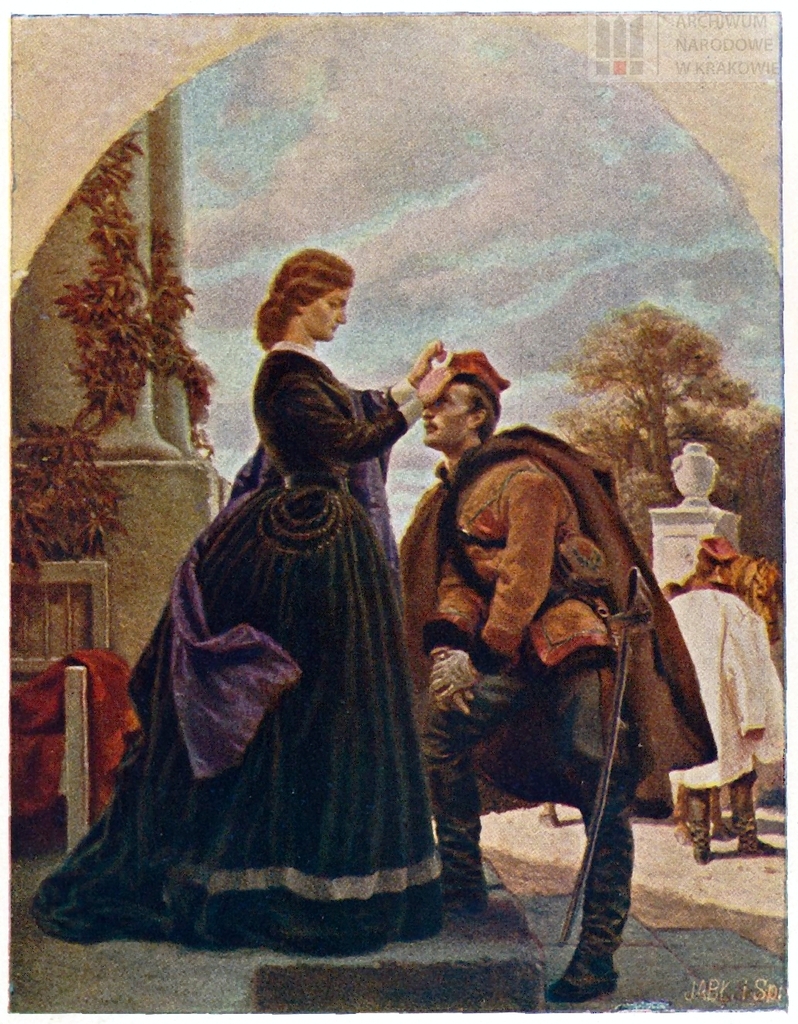

It was the longest and largest uprising in Polish history, covering the small Kingdom of Poland around Warsaw (dependent on Russia) and the eastern lands of Poland, ruled by Russia. Breaking out in the dead of winter on 22 January 1863, it lasted at least until the late summer of 1864, with some members still hiding out until the spring of 1865. It broke out in winter because the Russians imposed conscription upon young Polish men in the Kingdom of Warsaw. Men packed up their belongings and called for an Uprising instead. In the coldest month for fighting, the men were blessed by their women as poignantly shown in Artur Grotgger’s painting.

Battle without weapons

Although formed into typical military units and had hunting rifles and shotguns, they had an insufficient number of arms. Many insurgents expected to acquire a weapon from the enemy or buy it from abroad. Choosing guerrilla tactics as the only sensible option, they hid in woods and often fought with only scythes and swords. They were also lacking in artillery, using cannonballs made from wooden logs embedded with iron. Fighters were totally outnumbered by the Russian Army; the fact there were some victories is credited to their sheer determination to overcome the enemy.

Women and foreigners in the ranks

Approximately 200,000 people passed through the ranks, including women such as Lucyna Żukowska (above left) or Anna Pustowójtówna (above right). Anna used the pseudonym of Michał Smok and fought in several battles including the largest at Grochowisko on 18 March 1863, currently in central southern Poland. Nearly 7,000 participants took part on both sides in an extremely bloody battle but at least in this one the Poles came out victorious. Women at home supported the Uprising on a very large scale gathering funds and organising hospitals. They also looked after the families of those fighting, acted as couriers and organised false passports and hiding places for those on the run. No 19th century shrinking violets here!

Italian General Francesco Nullo, fought on the Poles’ side, falling at the battle of Krzykawka near Kraków and a French Officer Francoius Rochebrune created the fighting group Żuawy of Death – who always fought to win or to die and dressed in black coats with white crosses. The Szytelnicy (dagger brigade) also fought fearlessly and often brutally, assassinating Russian officials or those who betrayed them. At least 1200 battles and skirmishes were fought in total during the January Uprising.

The first Underground State

The idea of an underground Polish state was established, representing the country through the Provisional National Government and equipped with all the necessary attributes of power and law. The Government collected taxes, passed laws and had a secret state administration, divided into voivodships and districts. A Post office operated and underground papers were printed. It was an absolute blueprint for the highly efficient underground state set up during the Second World War.

Unsuccessful but fruitful?

“The idea of nationality is so powerful and makes such great progress in Europe that it will not be beaten” said the leader of the National Government, Romuald Traugutt, hanged in Warsaw in 1864. He was no doubt hoping that earlier revolutions in Europe would continue. Yet the Uprising did not manage to garner the support of all classes of society, some peasants rebelled against their landowners and there were moderates and revolutionaries amongst the Insurgents.

The Uprising had no chance of success against the much larger and well equipped Russian army and lost nearly one tenth of insurgents. Thousands more were deported to Siberia and some escaped to France and beyond. Towns were burned, taxes were imposed and property was confiscated forcing the remaining gentry into total poverty. And yet it ingrained in Poles a national consciousness to continue the struggle for independence. It gave artists a theme for patriotic works of art and played an important role in shaping attitudes and views in the Second Polish Republic (1918 – 1939). Famous authors took up their pens – Eliza Orzeszkowa wrote “Nad Niemnem” (on the banks of the Niemen) and Stefan Żeromski wrote “Wierna Rzeka” (Faithful river).

The spirit remained strong

Józef Piłsudski did not hide his fascination and commented ” The greatness of our nation was in the great epoch of 1863.” The spirit of the Uprising lived on in people’s hearts and minds despite the Russian recriminations for the next 50 years. In 1920, the reborn but weakened Polish state had to face the Russian Bolshevik expansion into the West. The peasant classes buoyed up by national fervour eagerly fought side by side with representatives of other social strata. Thanks to the unity of the Poles, the Russians failed to gain any territory and the idea of a free Poland became a reality.

This article first appeared on the website in January 2019

You may also wish to read:

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2