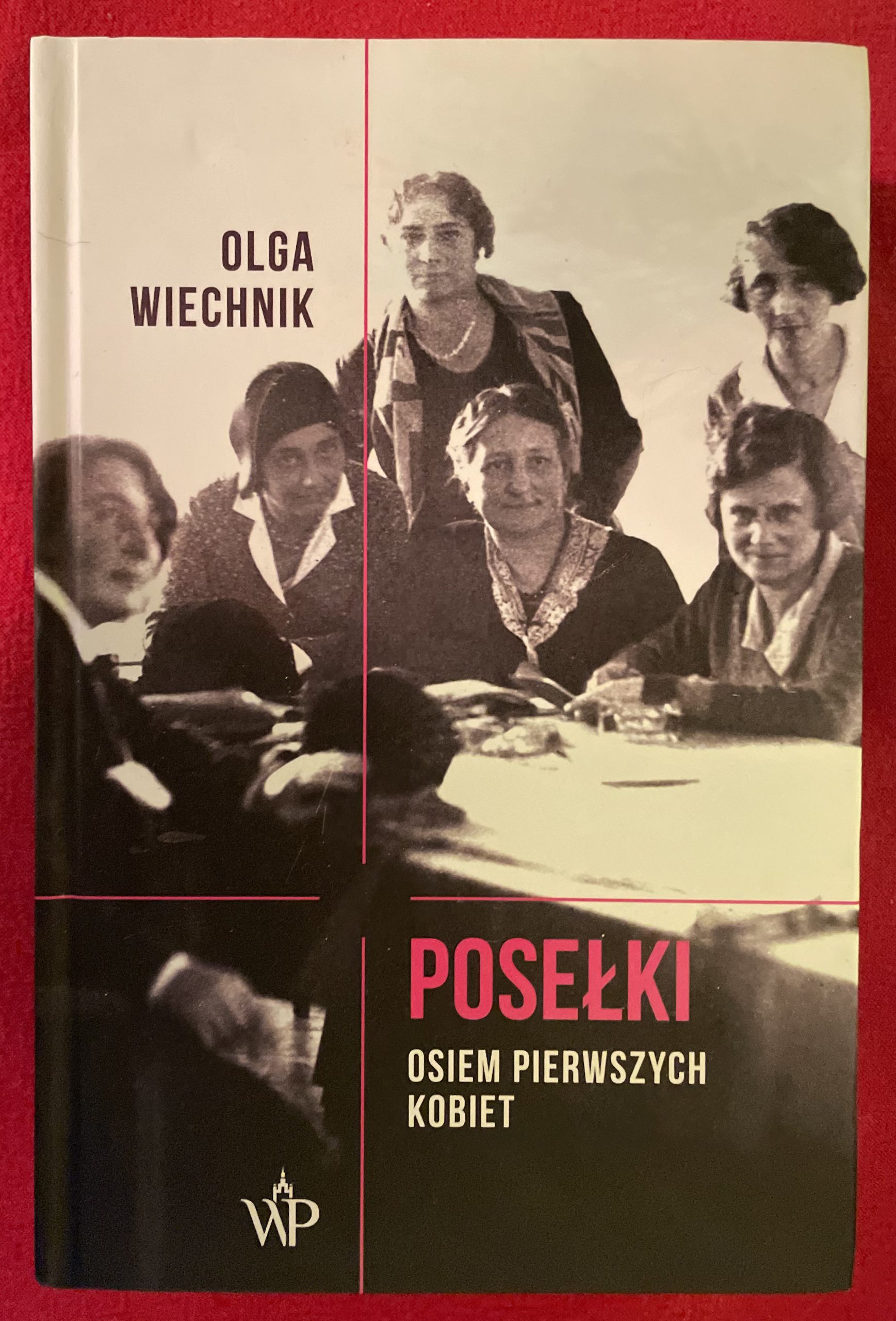

Few people today can name any one of the first eight women in 1919 who were elected to the first Polish Sejm of the II Republic following women receiving the vote. The female Poselki or Posłanki (MPs) don’t have statues or streets named after them; they’re not even on the school curriculum. Why is this? Perhaps it is because no one individual stands out? Yet these women are far from forgettable due to their talents and determination.

Zofia Moraczewska (centre left) at a National Women’s Organisation meeting/ Photo: Archiwum Cyfrowe

It has taken 100 years for this comprehensive book to appear about these women, written by Olga Wiechnik (sadly not yet in translation). The copious diaries of Zofia Moraczewska means the women speak for themselves from its pages. Yet when I bought it in Sopot Museum the assistant told me not many people buy it…

Unbelievable struggles for the vote

This amazing group of women lived within the three partitions of Poland until 1918, each partition had a different legislation, with more or less political freedom and the women’s groups within them had different strategies for fighting for the vote. This made these women’s obstacles huge, in addition to which all were engaged in the war effort. After Jóżef Piłsudski, as Chief of State signed the decree on November 28 1918 to give women the vote, the first national election with women candidates took place on 26 January 1919.

Women Voting for the first time /photo: Archiwum Cyfrowe

Inspirational

Gabriela Balicka-Iwanowska/ Photo:public domain

All were educated women with inspirational energy and initiative. The eldest, at 52 was Gabriela Balicka – Iwanowska, a doctor of botanical science. Irena Kosmowska university educated, was a newspaper columnist with a male pseudonym; Jadwiga Dziubińska was a headteacher; Anna Piasecka and Zofia Moraczewska were schoolteachers; Zofia Sokolnicka attended Kraków University and was active in a number of legal and clandestine organisations to educate young Poles; Maria Moczydłowska studied at Warsaw University and Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa was an activist among Polish emigrant communities. That was just the tip of the iceberg as they fought for social change alongside the minutiae of running households, four of them being married with children.

“These women usually combined politics with social activities, which could be educational, charitable or caregiving in nature” [IPN]

Clandestine underground and aid workers

Zofia Sokolnicka /photo: public domain

Irena Kosmowska /Photo: public domain

Zofia Sokolnicka, born into a patriotic family was gifted with excellent powers of memory. During World War I, she travelled abroad many times to meet members of the Polish underground organisation, carrying no paper documents, memorising reams of secret information. Irena Kosmowska, arrested in May 1915 for her anti-Russian publications and membership of the Polish Military Organisation, was sent to Saint Petersburg where she organised courses for refugees. During World War II, she was again arrested for underground activities and died in prison in Berlin. Zofia Moraczewska set up a workshop to sew uniforms for the Polish legions and her house was an illegal storehouse of weapons for them. Jadwiga Dziubińska carried food and clothing to soldiers, civilian prisoners and those exiled from previous uprisings in prisoner-of-war camps in Siberia, also organising funds to improve their appalling conditions. Anna and Gabriela taught in secret schools during the partitions.

Alcohol, Workers’ and Children’s Rights

Unfortunately women MP’s were tolerated rather than celebrated. Piłsuski opened the first Sejm with the words “Panie Posłowie (Gentlemen MP’s)” without mentioning their presence. Nevertheless, Zofia Moraczewska first spoke in March 1919 on the organisation of public health and infectious diseases. These women belonged to socialist, to centrist parties and to the right wing alliance of parties but campaigned for similar issues.

Rally to restrict alcohol photo:Archiwum Cyfrowe

Jadwiga Dziubińska Photo:public domain

Maria Moczydłowska -Muzeum Sopot

Gabriela fought for women’s civil rights and together with Maria Moczydłowska, the youngest at 33, fought to abolish the sale of alcohol which caused so much social strife. They had to make do with an act of 1920 restricting the sale of alcohol known ‘Lex Moczydłowska’. Sadly unsupportive male MP’s would go for a ‘Moczydłowska’ vodka in the bar. Maria also wasn’t averse to using her feminine wiles. She ‘fainted’ during a vote on land reform which her party supported but she didn’t!. Jadwiga concentrated on workers protection and education, preparing the Act on Agricultural Schools, 1920 to train agricultural smallholders. Franciszka was way ahead of her generation, campaigning about the harmful effects of smog and against beating children. The primary issues of the new Sejm were a new constitution, war on several fronts and organising the new nation but these women persevered with their causes.

No paper trace

Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa

Anna Piasecka/ Photo: Ziemia Pogranicza

Despite dying aged 98, no traces remain of Anna Piasecka. A widow with four children by 1920, she had taught and established the first kindergarten in the German partition and worked tirelessly for the Polish vote in the Pomeranian area which remained in German hands. Her niece says that as children they would watch her exercising in the morning in her 50s, doing the splits! Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa also left no letters, documents or memories shared with family though her magazine articles for Głos Kobiet (Women’s Vote) remain.

Since reading the book, I think of these women often, their incredible heroism, that they believe so deeply in changing the world and never give up. Their feminism was all encompassing, not just for the educated classes, it included social change, education and the improvement of conditions for the poorest. They had to continue the fight against fierce male dominance in the Sejm and it feels so much has still not been achieved. I find it achingly sad that most were forgotten and some died in poverty in the Polish People’s Republic without the recognition they deserved.

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2