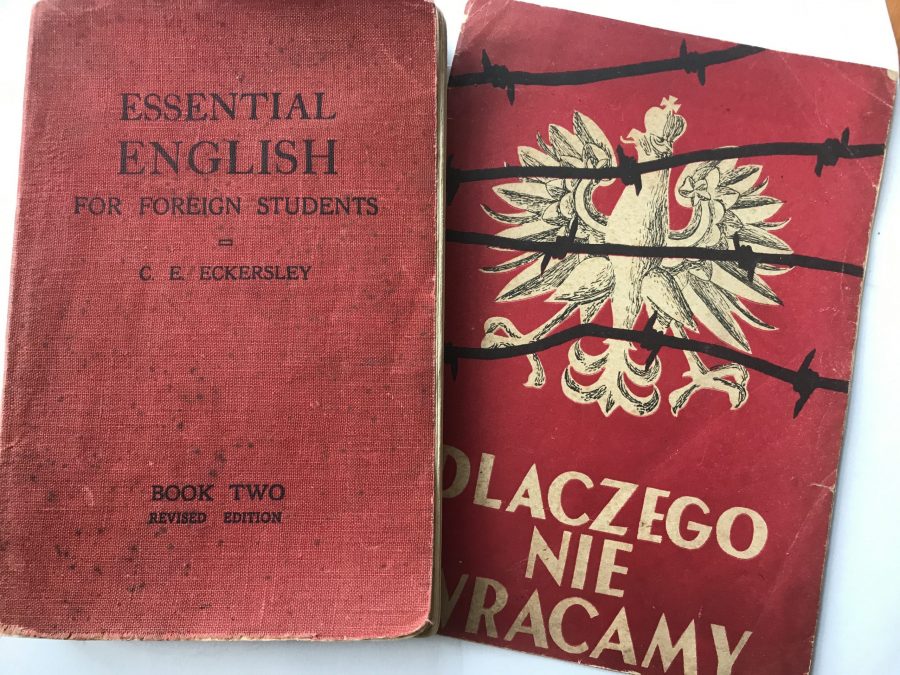

I have fond childhood memories of reading my mother’s copy of “Essential English for Foreign Students“, first published in the 1940s. It presented a very narrow view of English society and for the Polish arrivals in the fog and gloom of post-war Britain, the language and culture on display must have seemed very alien compared to their lived experience of pre-war Poland.

Lost in transition

There is a theory that learning a language is more than changing the words we use to communicate with others; it can be traumatic as it involves “transition of self” (1). To use a language, you also need to change how you behave to match the words. The author of Essential English for Foreign Students (C.E. Eckersley) uses a fictional foreign language teacher Mr Priestley and his wife as the narrators of his language course:

” I, too, get up soon after seven and go downstairs to help Susan with the work ……… meanwhile Lizzie cooks the breakfast. …. Mr Priestley joins me for afternoon tea in the sitting room – usually bringing one or two of his students with him.”

To ask new arrivals to understand this privileged life with cooks and maids was, I think, a bridge too far for many Poles; they had arrived after living through unimaginable terror, loss and sacrifice, housed first in resettlement camps and now cramped lodgings. Housing was scarce and rent high, often two or more single men would share a room or several families would live in one house.

It wasn’t just the language they had to grapple with, sizes for hats shoes and clothes were different to continental sizes. Weights and measurements also, not forgetting pounds, pence, shillings and half crowns, a far cry from metric Złoty and grosze. English dishes were vastly different, Polish food items unobtainable and the culture around it equally so. As for social niceties – how would you know how to address people when we Poles have the very useful formal Pan or Pani – in English you cannot use Mr or Mrs without knowing a surname?

It wasn’t just the language they had to grapple with, sizes for hats shoes and clothes were different to continental sizes. Weights and measurements also, not forgetting pounds, pence, shillings and half crowns, a far cry from metric Złoty and grosze. English dishes were vastly different, Polish food items unobtainable and the culture around it equally so. As for social niceties – how would you know how to address people when we Poles have the very useful formal Pan or Pani – in English you cannot use Mr or Mrs without knowing a surname?

Something as simple as a formal greeting: “how do you do?” is also more complex than at first sight:

JAN: What ought I to say when I am introduced to someone?

MR PRIESTLEY: Oh just “How do you do?”

JAN: But it seems nonsensical. I ask them a question about their health and they don’t give an answer; they ask me a question which I don’t answer.

MR PRIESTLEY: Yes, I suppose it is rather strange, but we don’t think of “How do you do?” as a question – it’s just a greeting. If you really wanted to know about a friend’s health you would say, “How are you?”.

Integration

Integration

The 1947 Polish Resettlement Act provided Polish refugees in the UK with many entitlements including some types of employment where they could learn a smattering of English on the job. It tended to be the men who were taught basic English in resettlement camps for soldiers; women didn’t always have the same opportunities.

Importantly, transitioning into another culture wasn’t something Poles necessarily wanted to do immediately; their needs were complex. A psychologist who has worked extensively amongst Poles said:

“They lost their homes, their country, their culture and their families… they often found the pain of learning English unbearable. They were hanging on to their past by using their native language. This was considerably more common amongst East European women than men“( 2)

Photo: Sikorski Museum

Although the Committee for the Education of Poles, part of the Resettlement Act, recognised that young people needed to gradually become acclimatised to British life and so maintained Polish boarding schools for several years to help integration, adults or those needing to support their families didn’t have this luxury.

“The problem of communication is this, that the Polish people here, with a few exceptions, didn’t see any need in learning the English language in the very beginning….. I think it is also true that some Poles lived with the hope that one day, sooner or later, the Polish question would be resolved and everybody would kind of return, so what’s the point?”(3)

Different worlds

Despite some hostility to the Poles, many Anglo-Polish societies sprung up, helping them to become accustomed to English or Scottish culture and the Polish Soldier’s Daily ran articles on how to behave in shops or to tone down Polish lavish hospitality for British friends. One academic identified the Polish language as having the status of a core value, being so much more than a language (4). For those engaged in political meetings and activities it was a vital element of their lives, so learning just enough English ‘to get by’ would suffice.

Polish women taking tea – photo held by the Imperial War Museum

This often meant that children, attending English schools became interpreters for their parents, learning to shoulder responsibilities at an early age. Perhaps you were one of them? For the lucky Poles who could practice their profession and those able to access further education, the English language was a key to being able to work and prosper. For others, it was something to be kept to a minimum outside of the home, a threat to Polish identity, leading to a great separation between their Polish community life and the host English culture,

“It was like two different worlds – an English world and a Polish world. I walked into the house and I became Polish” (5)

Over the following decades, as the world around ex-soldiers and their families became more familiar, they started to pepper Polish conversations with English words: who hasn’t heard of fiksować (to fix) or daj lifta (give me a lift). Still it wasn’t an acceptance of their fate or of English as their first language for communication (as it became for many of us children and grandchildren), and who could blame them? Visiting Poland in later years they often felt foreigners there and foreign here, lost between the two worlds.

Did you recognise this divide in your early life? I wonder how it affected your knowledge of the English language? I for instance never learned to use English idioms. Do write to me and let me know. I’m always interested in people’s memories.

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2