The deportation of Poles by the Russians to slave labour camps in the Soviet Union during WWII, is well documented if not widely known. You can read the testimonies here. Yet only a fraction of the approximately 1.7 million deported Poles managed to escape and went on to fight like lions at Monte Cassino. I know from my own family’s story that this was an epic journey, survival depending on one’s wits and many died along the way.

How were they released?

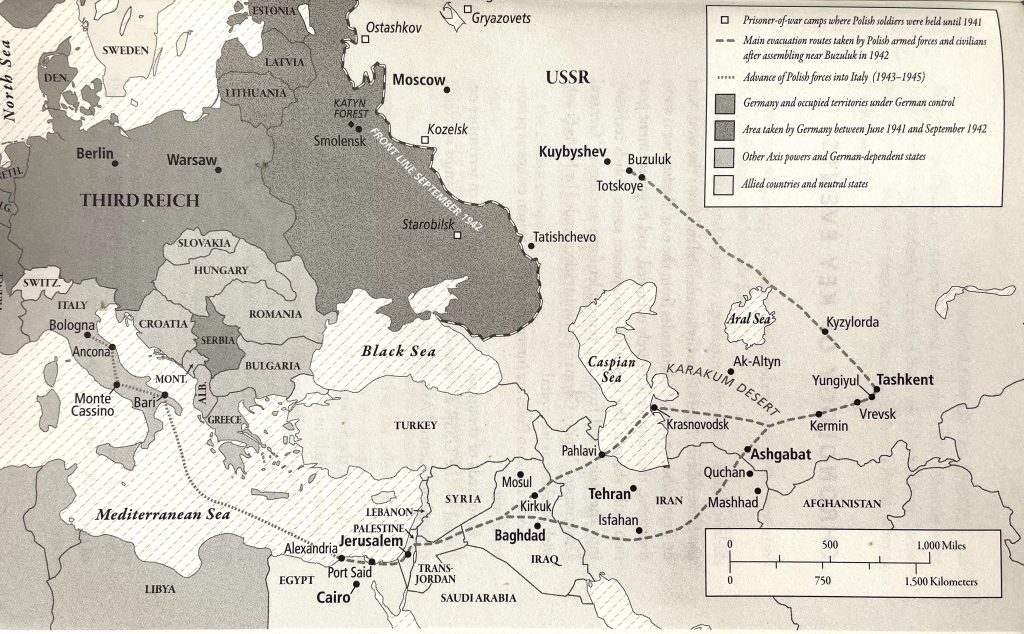

Evacuation route from Buzułuk. Józef Czapski – Inhuman Land Searcing for the Truth in Soviet Russia 1941 – 1942. First pub. 1949

In July 1941, after nearly two years of war, Nazi Germany attacked their former ally, the Soviet Union. General Sikorski took this opportunity to negotiate a compromise with the USSR ambassador Mr Majski for the Poles’ release, sealing it with a visit to Stalin. He knew thousands of officers were in captivity and more men from Soviet labour camps would volunteer to form a Polish army. This would support the Russian front under General Anders, also recently released.

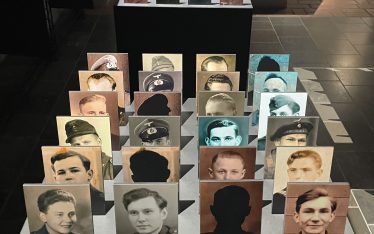

The Polish embassy based in the south of Russia, set up a network of trusted officials at major train stations and cities to direct these men from camps to army enlistment sites in Buzułuk, Tatiszczew and Tockoje. Food, medicines and clothes stores were set up. Still, communication took time to reach many labour camps and some families, deported for having an officer in the family, decided to stay put hoping that their menfolk, interned elsewhere, would find them. As we know, they had already been murdered on Stalin’s orders in the Katyn forest and Polish army officials were puzzled by the lack of officers arriving for registration.

Confusion and difficult decisions

Forgotten Force – Polish Women in the Second World War (facebook)

Civilians headed south from all directions, by river from Siberian logging forest camps, then train, from the gold mines in Kazakhstan. Selling their last possessions to travel, often in open cattle trucks, their routes were not always direct, nor were they always allowed to leave the Soviet camps.

“Not many of our people, especially those with young families could afford to take the chance of escaping, as this would have deprived the rest of their family of their small bread rations…. nevertheless some young boys took the chance one night and made a run for it. heading for the nearest railway station….Meanwhile the authorities of our Camp No. 113 tormented the parents for letting their sons leave the labour camp.”(Veronica Aleksiewicz-Zagorska, Siberian Scars, Stoke-on-Trent,1998)

THE POLISH ARMY IN THE SOVIET UNION Probably taken at Buzuluk in Russia, 1941. Copyright: © IWM.

“It was a long and very difficult journey…Gradually we travelled south through Russia, through Tockoye and Tashkent to Kazakhstan, which was the first time I saw camels. We lived on the floors of disused buildings or in tents.” (Lola’s story ©Bradford Museums and Galleries).

Wherever trains went, people would crowd onto them. Often stopping in the middle of nowhere, food was only available by trading what few possessions they had left, or stolen from nearby fields. The journey often took several months, using the trusted Polish officials as lifelines, to follow south.

” They were always debriefed on arrival at a particular unit. The place and date of their deportation and the destinations were noted for the records, as were details of other people whom they had travelled with or met, while living in Russia.” (Helena Bitner-Glindicz – A Song for Kresy 2017). Helena arrived with her family in G’uzor Uzbekistan, truly horrified at the number of soldiers and civilians dying of tyfus, dysentry and malaria

Window of opportunity

Little did they know that their window of release was shortly to shut. The Russian government resented feeding and supplying their former prisoners. Rations received from the Russians authorities, were one third, occasionally two thirds of those required for the amassed army of over 70,000 and certainly not enough to improve the soldiers’ conditions to be trained effectively. Finally, with Anders refusing to send the army to the Russian Front, agreement was reached with the British for the army to move south to Kirgistan, Kazachstan and Uzbekistan before being evacuated and joining the Eighth British Army in the Middle East.

THE POLISH ARMY IN THE SOVIET UNION, 1941-1942 Probably Buzuluk, Russia. Copyright: © IWM

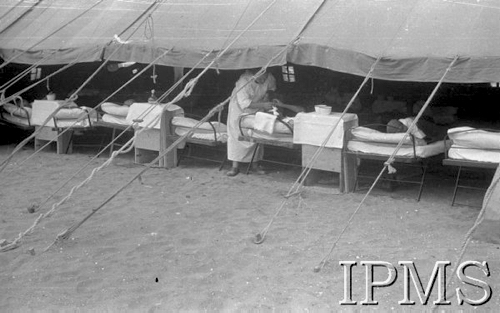

“The average number of people sick was more than 69%…our people lived in Uzbek and Tatar tents and shelters dug in the sandy fields…. louse-infested and already infected, large numbers came pouring in there to join the army. There was no underwear…. some two thousand people lived under the open sky when at night there were still frosts and snow.” (Józef Czapski – “The Inhuman Land Searching for the Truth in Soviet Russia 1941 – 1942” New York Review Books 2000.

As relations with the Russians exacerbated, General Anders called for the desperate civilians including many orphans to be evacuated alongside the army, despite British and Soviet resistance. Just a year after the agreement for release, in July 1942 the Russians started to close the network of Polish communication points for refugees, arresting officials and confiscating documents.

In one of the camps formed for artillery troops, Kara-Suu in Kyrgyzstan, soldiers shared their meagre rations with orphaned children living next to the camp whilst civilians camping outside, knowing that proximity to the army gave them a chance of salvation. In this camp many attended mass for the first time since being deported, as even saying prayers had been forbidden by the communist authorities.

1942-1944, unknown. Fot. NN, Instytut Polski im. Gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie [Album nr 5/B1]

O Lord who art in heaven, Reach out with a righteous hand! We call to you from foreign lands, for a Polish roof and Polish weapons.”

In tears they sang of hope, of their country crushed by sword and asking for deliverance. They had no idea how much further they would have to travel to reach that home. As we know, for most, it became inaccessible for decades.

Finally, release

The first evacuation of Polish people from Krasnovodsk in the USSR to Iran across the Caspian Sea took place in March 1942, those destined for the air force or navy with their families, then the bulk during August 1942. A condition for families being accepted was having a member in the army so some young men “adopted” family so they could leave.

April 1942, Pahlewi, Iran. Fot. NN, Instytut Polski im. Gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie [album negatywowy B-I IRAN] – płachta 5

Arriving on the train at Krasnovodsk there was a lack of food and water and a further walk to the port surrounded by bodies lying exhausted or dead. Even now there was uncertainty as to who could leave. Soviet officials stood by the ship reading out names of those allowed to leave.

Pahlevi Paradise

After 36 hours on the trawlers, they arrived on the beaches of Pahlevi, Iran to camps organised by the British. Row upon row of hospital tents stretched out for kilometres on the sands. Rudimentary shelters made of canes and palm leaves were built for those not requiring medical attention.

April 1942, Pahlewi, Iran (Persja). Fot. NN, Instytut Polski im. Gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie [album negatywowy B-I IRAN] – płachta 4.

(War Diaries of QAIMNS Acting Principle Matron Lieutenant Colonel Hughes, Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps, qaranc.co.uk )

These families were the lucky ones, they had been through hell but more heartache awaited them. Soldiers – brothers, sisters, daughters, sons, husbands, fathers, mothers and wives travelled through Teheran onto the Middle East for army training, whilst their families were sent to India and Africa for however long the war would continue. The only testimony that remains of the oddyssey of those left behind is the string of Polish cemeteries across the Soviet Union and beyond.

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2