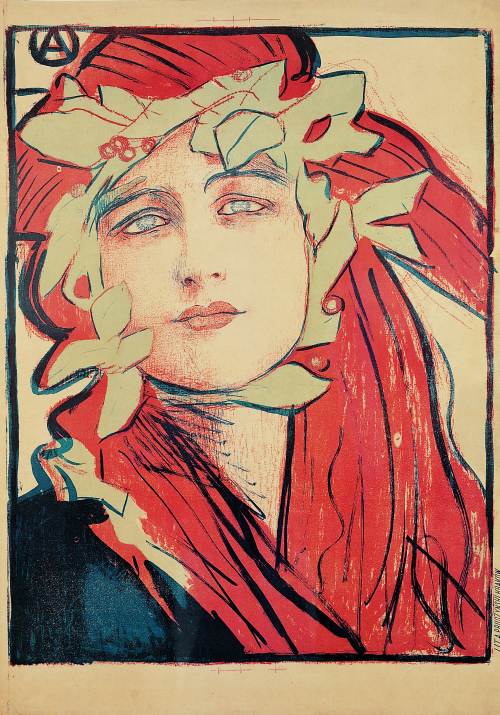

I’ve always loved this poster by Teodor Axentowicz for the 1898 Society of Polish Artists exhibition. I took inspiration from it for Polish at Heart’s brand colours. The woman’s head intertwined with berries and leaves demonstrates to me the spirit of women, defiant, brave and at one with nature. It also says much about the cultural and political background out of which the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) artists emerged and a refreshing change in Polish art to the Jan Matejko battle scenes. Of course they were inextricably linked as he taught many of the artists of this movement centred around Kraków from 1895 – 1914.

A people in despair

Poland at the time had been occupied by three neighbouring countries for over 100 years and Norman Davies has described it as “ a memory from the past or a hope for the future.” After more than one failed insurrection against the worst of the three partitioners, Russia, the people were cowed and divided.

Jan Matejko Polonia 1863 / public domain

Jan Matejko’s Polonia painting (a shackled woman personifying a nation brought down) had a profound effect on the young artists he taught. Influenced by and part of the emerging Art Nouveau movement in Europe which personified ‘art for art’s sake’ they began to use art to remind Poles of their traditional roots in the land. Seeing art as beauty in itself led them to move away from Poland’s tragic past in their subject matter and seek inspiration from the villagers’ lives and folk art, seeing the people of the land as the heart of Poland’s renewal in fulfilling their dreams of freedom.

Freedom in Kraków

Part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Kraków had the freedoms for Polish culture to flourish, having its own Council and Mayor since 1866. From that time, standards of living improved, the Polish university was expanded and Kraków started to resemble a modern city. The School of Fine Arts gained autonomous status with Matejko as its first Director. Having close links with Vienna and Paris, many Polish artists joined a group including Gustav Klimt in producing highly stylised and influential works of graphic art but for subject matter it was rural life that drew them.

Kopanie Buraków’ (Digging Beets) by Leon Wyczółkowski, 1893, photo: National Museum in Kraków

Rural life

North west of Kraków was the village of Bronowice Małe (now one of its suburbs), a typical village with blue-painted cottages set amongst orchards. At the time, authors such as Eliza Orzeszkowa or Bolesław Prus had begun to write about the life of peasants and the artists followed suit, focusing on the life of villagers, often also influenced by light and shadow of Impressionism. Matejko encouraged their move away from dark colours and historical scenes, saying:

„Do was należy powietrze i słońce, ja zaś zostanę ze starymi królami…”

“The air and sun belong to you, I will stay with the old kings”.

Lidwik de Laveaux – Dwie wiejskie dziewczyny 1889/ two village girls/ public domain

The artist Władyslaw Tetmajer moved to Bronowice and married a villager in 1890 building a dworek (manor house) for his new family. Soon after painters, poets, writers and politicians visited him and established their studios there.

Teodor Axentowicz – Kołomyjka/Oberek. Folk dance in front of the house, 1895,

Lucjan Rydel a poet, married another local girl in 1900 and the wedding feast at this dworek was the inspiration for Stanisław Wyspiański to write his famous play “Wesele”‘ – the “Wedding”. A series of ghostly apparitions are interpreted by each of the play’s characters as the embodiment of their unfulfilled dreams of independence. Writing this lost era into Polish history, he wanted to show that divisions between rural and city life still exist but must be erased before Poland can be free.

Józef Chełmoński – Bociany 1900/ Storks/ Public domain

The artists’ obsession with rural life, their habit of dressing as peasants or painting picturesque rituals as the ideal Poland created great art but did little to highlight the problems of rural life, especially poverty, as in Chełmoński’s painting above, of peasants tending cattle with dirty feet from lack of footwear. For the artists, the meadows demonstrated idyll, gaiety and freedom, the hidden beauty of the nation. Their focus on flowers heralded a new bloom for the country after a difficult time, like a flower, the country will mature and grow into something new.

Symbolic representations

Jacek Malczewski – Ojczyzna – Homeland/ part of a Law – Homeland – Art triptych / public domain

Very influenced by Matejko’s romantic and patriotic paintings, Jacek Malczewski’s art moved into symbolism, presenting his homeland as a proud, thoughtful mother, on the move like a pilgrim, against a traditional Polish field of flowers and grain, the son with a pained expression, the daughter holding shackles. These floral motifs also appear often in the paintings of Wyspiański, Axentowicz, Chełmoński, Gierymski, Hofman, de Laveaux, Sichulski, Tetmajer and Wodzinowski.

Churches and stained glass

Stanisław Wyspiański focused on rural life and nature in portraits, polychromes and stained glass windows in churches, book covers, vignettes and posters. Also married to a village girl, he wrote: “I sit all day in Bielany, drawing plants”.

Stanisław Wyspiański autoportret 1902 /public domain

Helping Matejko to renew the interior of the Kościół Mariacki in Kraków’s market square, together with Józef Mehoffer they painted that starry sky and walls full of motifs. He went onto design the interiors of St Francis’ basilica, with colourful floral patterns reflecting St Francis’s love of nature and moved into stained glass with his image of ‘God in the Act of Creation’. This focus links the artists to the Arts and Crafts movement in the UK as well as those who based their designs on Góral – Highlander folk art and architecture. You can read more about that in the article about the 2021 exhibition.

Some of Wyspiański’s works intended for the Wawel cathedral were seen as too controversial and are now featured in the Wyspiański Pavilion. Both these and the designs in churches still look very modern despite being painted over 100 years ago.

You may wonder what these artists did after 1918. Although some died before independence, others experienced war in the trenches and many developed their art in different directions. Their love of rural idyll had lost its relevance in a rapidly industrialising country. They never fell into oblivion, however and Wyspiański’s work was later banned by the Nazis, to be destroyed if found, so their art lived on as a Polish national treasure.

There are many places where you can see the art of Młoda Polska in Kraków, the National Museum Main building, the newer Stanisław Wyspiańśki museum, the Wyspianski Pavilion on Grodzka Street, St Francis Church and Rydlówka museum in Bronowice, scene of the play ‘Wesele’ and the often visited Jama Michalika on Florianska Street and the Noworolska cafe in the Market Square where the artists would meet. My favourite place in Kraków, however, is the Józef Mehoffer house at ul Krupnicza 26. Preserved exactly as the artists would have known it when Mehoffer entertained them in the drawing room, you are immersed in the atmosphere of the turn of the century, with many of the Mloda Polska paintings on the walls. It also has the most delightful cafe in the gardens behind.

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2