“To Moscow, to Moscow” said the sisters who languished at home, bored of their country life in Chekhov’s “Three Sisters”. The long days of June do seem to go on forever. They are perfect for the kind of unhurried, afternoon garden tea parties that Poles, living in the Kresy border regions, would have often enjoyed at this time of year. Although the samovar was a Russian invention and features in all Chekhov plays, many Polish homes living under Russian rule in the 19th century adopted them and made them part of their lives.

From Lwów and beyond

I bought an ancient samovar from a street trader in Lwów for 10 US dollars in 1998, during a journey across Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania with friends. I put it in my rucksack and filled it with clothes for my onward journey. Unfortunately, on the plane home it suffered a bit of a kicking. Over the years I have tried to clean it up a bit and one kind man did knock out the dent and replaced the top handles with newly turned wood, but it’s still not back to its former glory.

I bought an ancient samovar from a street trader in Lwów for 10 US dollars in 1998, during a journey across Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania with friends. I put it in my rucksack and filled it with clothes for my onward journey. Unfortunately, on the plane home it suffered a bit of a kicking. Over the years I have tried to clean it up a bit and one kind man did knock out the dent and replaced the top handles with newly turned wood, but it’s still not back to its former glory.

How were samovars used?

The theory goes that water was heated with the help of glowing charcoal, placed into a special pipe in the middle of the samovar. If you lived in the countryside, pine cones or wood was used. So armed with this knowledge I took it outside for its first use in possibly 100 years.

I lit some wood and waited. What I soon realised was that my samovar is also missing a pipe or chimney extension, which channels the smoke up and away as the coal or wood burns. So we were all immediately coughing from the smoke in the still, afternoon air. Not only that, I was missing the brass tray underneath, which was used to collect the ash, falling through the grate under the samovar.

With a bit of improvisation I got over the problem of the smoke and the ash, and amazingly quickly the water was starting to boil. Sadly I couldn’t get beyond this step as the tap on my samovar refuses to open.

So back to the theory, once the water boils, you pour a little water into a teapot with the tea leaves and place it on top of the samovar to brew. To take your tea, first transfer hot water from the tap and add this to the strong essence in the teapot. Your tea is now ready.

For Polish homes of the gentry, in the dworek, tea was prepared in the Kredens (an ante room) next to the dining room, such as this one from the regional museum in Siedlce. Plates were placed on the table and decorated before being served on the table and the samovar was prepared. Russian tea was drunk most often with plum jam or a cube of sugar kept in the mouth.

As one Pole, Tadeusz Zubiński recalls in reminiscences of his family’s childhood “I still prefer to drink tea with preserves, as I hope, our people still do in the East. Somehow I can not get used to sugar in tea. I remember to this day that we drank our tea at our home in Landarów near Wilno. Boiling water was taken from the samovar and tea taken with gooseberry jam was the best, though it could also be raspberry”

As one Pole, Tadeusz Zubiński recalls in reminiscences of his family’s childhood “I still prefer to drink tea with preserves, as I hope, our people still do in the East. Somehow I can not get used to sugar in tea. I remember to this day that we drank our tea at our home in Landarów near Wilno. Boiling water was taken from the samovar and tea taken with gooseberry jam was the best, though it could also be raspberry”

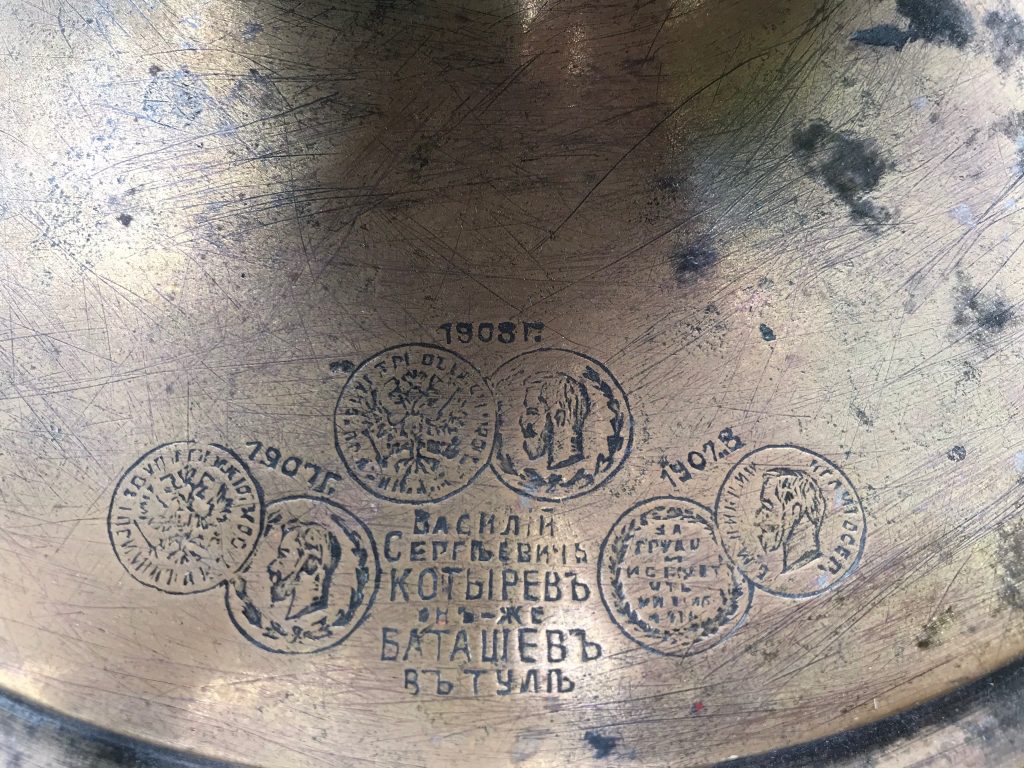

Where were samovars made?

Tula was the center of the Russian samovar industry. Located 120 miles south of Moscow, it was a major centre of skilled metalworking until the 18th century when the craftsmen of the area decided to use their metalworking talents to create samovars instead of cannons. Two factories specialised in producing samovars, the Voronzov and the Batashev factory. Over time competitions were set up and copies of medals won at them were engraved onto the fronts to show how successful that model was. Mine clearly was, as it has about 12 medals from 1895 through to 1908 on the body and the maker V.S. Kotirev (Batashev) stamped on the lid. So I can date it to before WWI as the stamps continued beyond. After the Russian Revolution however, the stamps featured the hammer and sickle. Eventually they started to make electric samovars which were much easier to use and still grace many a Russian home, used for family occasions.

Mine clearly was, as it has about 12 medals from 1895 through to 1908 on the body and the maker V.S. Kotirev (Batashev) stamped on the lid. So I can date it to before WWI as the stamps continued beyond. After the Russian Revolution however, the stamps featured the hammer and sickle. Eventually they started to make electric samovars which were much easier to use and still grace many a Russian home, used for family occasions.

Home and hearth

In Russia, taking tea with a samovar was the cue for a long chat and it became a 19th century symbol of the home and hearth, a time of comfort and relaxing. In Poland, tea was initially treated as a healing herb (herbata lipowa) as most people drank coffee, but black tea began to gain popularity on a wider scale from the 1850s at the same time as the introduction of samovars. These were used right through to the inter-war years. Imbryki (kettles) however continued to be used in the Austrian and German areas of Poland.

The Sunday (1884), by Russian painter Alexei Korzukhin

So when you think of your Polish family living in the Kresy in the 19th century, no doubt the samovar had pride of place on the dinner table, or as here, in the countryside during a long summer’s day. And whilst it might all seem like an idyllic life, remember the Three Sisters who were weary of it and yearned for city life…

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2