Of the many accounts I’ve read about the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944, these words hit me hard. They were recorded by someone who many years later, sat with the surviving soldiers during a commemorative event.

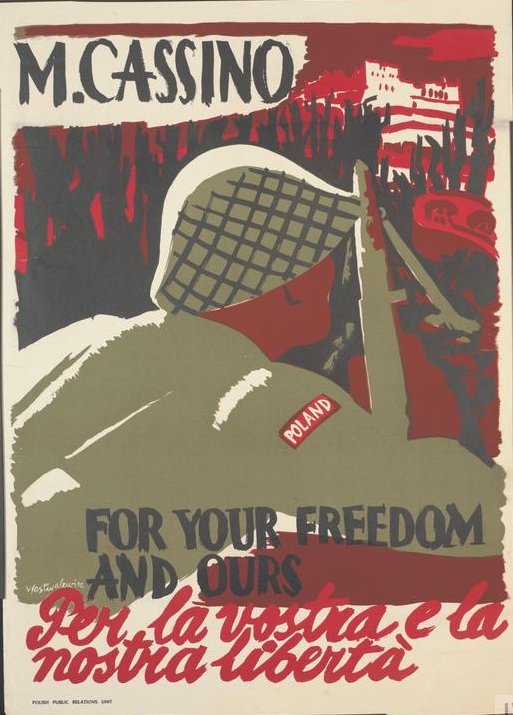

Polish soldiers who fought at Monte Cassino were no ordinary conscripts, drafted and sent to Italy. Most had been forcibly removed from their homes by the Russians, sent to Siberia to labour camps, endured near starvation and escaped on foot to Iran to join the Free Polish Forces as part of the Allied effort.

There are horrific accounts of the battle by men who survived; but I also want to remember those that perished. Men such as Ferdynand Ciastko, who did not live to see the Polish flag flying from the monastery, but lies in the cemetery.

Killed four days into the battle, he had not even celebrated his 18th birthday when war broke out in 1939. Ferdynand was an Ułan of the Karpacki Pułk Ułanów, (a Lancer from the Carpathian motorised Cavalry Regiment). He had spent his brief adulthood preparing to liberate not just Cassino, but Poland. We don’t know his journey, we don’t know who he left behind at home. The war for men like him was full of suffering and horror – perhaps tempered by hope and faith in a future, free Poland. Sadly that wasn’t to be. At the time of the battle and unknown to Ferdynand, Allied leaders Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin had already decided the fate of his home in the eastern lands of Poland.

Where is Monte Cassino? What happened?

The magnificent Abbey of Monte Cassino was built on a rocky hilltop in 529 AD by Saint Benedict. Despite being repeatedly sacked or destroyed in its early history, it survived in different forms throughout the ages. Geographically, it lies about 130 kilometres southeast of Rome, dominating the nearby town of Casino and the entrances to the Liri and Rapido valleys. Strategically, its importance lay in this, its location: guarding as it did the route to northern Italy. In 1944, as the Allies pushed towards Rome and with the German army in retreat, the hilltop and entrenched defenders were identified as a prime target for massive Allied bombardment in one of the fiercest actions of the Second World War.

Photo:Ryszard Szydło/ @rsimages

Why were the Poles there?

The II Korpus Polskich Sił Zbrojnych na Zachodzie (Polish II Corps) was created in 1943 from various units fighting alongside the Allies, either in the Middle East or in the army formed with those evacuated from Russian labour camps. In November 1943 these troops, numbering about 50,000 soldiers were trained for mountain fighting and transferred to Italy ahead of the battle. Their task was to push the Germans back towards the North of Italy and do what had been tried several times without success: to break the Gustav Line of defence which stretched from east to west across the whole of Italy.

How long did the battle last?

The action wasn’t just one battle but a series of four assaults by the Allies against the Germans, that had begun in January 1944 after the Allies had landed in Italy the previous September. The forces of several Allied countries had attempted since mid-January to capture this German-held fortress. In February hundreds of tons of explosives were dropped by bombers, obliterating the Abbey, in the belief that it was occupied by German troops. Sadly, it seems this was not true but the German forces immediately utilised the rubble for cover making it even harder for Allied troops to make progress up the perilous slopes.

.Copyright: � IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/37549

What was the battle like?

“All the trees were naked, stark and leafless. Route 6 dwindled into a ‘sheep track’ which wound its way through shell craters, bomb craters, and the gaunt remains of houses. All the way up this track was a mass of kit, blankets, bits of clothing, boots, steel helmets. The whole of the area in front of the town was a ghastly marsh, caused by lack of drainage and the bombs and shell which had blown everything to pieces. All the craters have filled with water, which stank horribly and were very often a watery grave. Down this grim avenue were many bodies, which had been untouched for weeks, a grim spectacle.“

“I looked up at the Monastery, a mass of jutting rubble. Every single tree on the shell-shattered mountain face below the Monastery was stark and naked.”

Major Hardy Parker was with the 2nd Battalion Royal Northumberland Fusiliers

The night before the final attack, led by the Poles General Władysław Anders spoke to his troops saying “let the spirit of lions enter your hearts” and…”go and take a revenge for all the suffering in our land, for what you have suffered for many years in Russia and for years of separation from your families!”

Map of the assault on Monte Cassino May 11 – 19th 1944 Lonio 17 CC by 4.0

The first part of the assault led by the Poles began on 11 May 1944. It opened with a massive bombardment manned by soldiers of many countries, and the task of the Poles was to gain the Abbey by first gaining hills no 593 and Phantom Ridge. On 17 May, they launched their second attack on Monte Cassino. The fighting was fierce and often hand-to-hand. The Poles, with little natural cover were under constant fire from the German positions so the first soldiers fell quickly. As the Allies linked up and squeezed their supply line, the Germans slowly, firing to the last, withdrew from the mountain. On the highest rocks, the Polish survivors were so battered that it took some time to find men with enough strength to climb the few hundred yards to the summit.

A patrol of the 12 Pułku Ułanów Podolskich (Podolski Regiment) entered the ruined Abbey on 18 May and Kazimierz Gurbiela raised the Polish flag, followed shortly by the British flag and plutonowy (platoon leader) Emil Czech, rushed to the summit despite retreating fire to play the Hejnał Mariacki (Kraków Anthem). For the soldiers it was a huge victory, despite the losses “from being prisoners in Russia, now we managed to show the world that we can fight.” said one soldier.

How many people died in the offensive?

The loss of life was massive across the whole campaign with the Allies losing 55,000 soldiers and an estimated 20,000 killed and wounded German soldiers. The Poles lost about 1000 soldiers with 3000 wounded and 345 missing in action.

Where are the cemeteries?

In 1945 a Polish cemetery was built on a flat area known as the “Valley of Death” between Monte Cassino and hill no 593, in the place where the main Polish attack went through. Designed by architects Jerzy Skolimowski and Wacław Hryniewicz and supervised by surviving fighter Roman Wajda, it forms a cross, guarded by two huge eagles with hussar wings sculpted by Cambelotti. Over a thousand crosses recall the sacrifice of these young men who fought and died for freedom and peace, together with their leader General Wladysław Anders, who was buried with them in 1970, followed by his wife Irena in 2010. In the Commonwealth War Graves lower down the mountain lie men from Britain, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and India. The American cemetery lies in Nettuno and in Caira, north of Cassino, 20,000 crosses mark the graves of the Germans.

Who wrote „Czerwone Maki na Monte Cassino (Red poppies on Monte Cassino)“?

Feliks Konarski (known as Ref-Ren) wrote the song with Alfred Schutz on the eve of the battle and it was sung on the day of victory for General Anders: “For the first time, singing “Red poppies on Monte Cassino”, we all cried. Red poppies, which bloomed over night, became one more symbol of bravery and sacrifice” said the author in his memoirs. It quickly became one of the most well known Polish war songs, sung by the singer and actress Irena Anders, the General’s wife.

The red poppies on Monte Cassino

Drank Polish blood instead of dew…

As the soldier crushed them in falling,

for their anger was more potent than death.

Years will pass and ages will roll,

but traces of bygone days will stay,

and the poppies on Monte Cassino

will be redder for Poles’ blood in their soil.

What happened afterwards?

Allied forces captured Rome soon after, on 4 June 1944. The Polish II Corps carried on fighting with distinction most notably in the Battle of Ancona and the Battle of Bologna during the final offensive in Italy in 1945. Rebuilding of the Abbey started during the 1950s and it was reconsecrated in 1964.

When is the battle commemorated?

The SPK (Polish Ex-Servicemen’s Association) and the Polish Scouts all over the world have returned to Monte Cassino, year after year to remember the sacrifice. The government of Communist Poland played down the event and only since Poland regained independence, has the Prime Minister of Poland or one of their Ministers attended, together with Polish schoolchildren to pay homage to those who died and lay flowers on their graves.

In 2014, Prince Harry visited together with Donald Tusk, the then Prime Minister of Poland and was visibly moved by the sacrifice. And yes, I was there too as well.

So how will you remember the dead of Monte Cassino?

Many of us have relatives who lived through it. My uncle was in the tank regiment and my grandfather in the guards battalion stationed behind the front lines, but for all Polish soldiers at the time it was a sign of great hope, and those poppies a symbol of their fervour. I have picked poppies every time I have been on Monte Cassino but you can’t be there every year, so this is why I love them and always have them in my garden – the plants grow strong and thick in May, the buds appear from nowhere and suddenly bloom with vibrant resplendent colour, yet only last a few days before a carpet of red adorns the ground. I never know which plant will survive one winter to the next, yet once it has, I know it will bloom with fierce strength.

And that is how I choose to remember Ferdynand Ciastko and his brother soldiers; for the freedom they believed in and died for.

And that is how I choose to remember Ferdynand Ciastko and his brother soldiers; for the freedom they believed in and died for.

”For our freedom and yours, we soldiers of Poland gave our soul to God our life to the soil of Italy our hearts to Poland”

This poem inscribed into the gates of Monte Cassino’s Polish war cemetery reminds us of the Poles’ historical quest for freedom in foreign lands.

You may also wish to read:

the-battle-of-monte-cassino-what-happened-next-for-the-poles

Why it took 60 years for the Poles to join the Victory Parade

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2