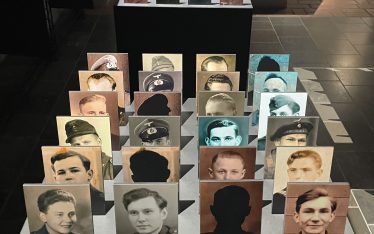

It is 80 years since on 10 February 1940, over 1 million people were sent from the Eastern borderlands of Poland to slave labour in Soviet Russia. A few survivors recorded their memories to ensure the crime is not forgotten. In 1940 families were already living hard lives, often like my grandparents recently turfed out of their house to make room for soldiers. Still, no one expected that trains with cattle trucks were being prepared for hundreds of thousands of people, taking them away at gunpoint in the middle of the night, never to return again. Packed tight into trucks – these Poles were not heading for Nazi concentration camps but for Soviet labour camps in the depths of winter, in record-breaking temperatures of 40C. “…Because the average life span in a gulag did not exceed one winter, everyone knew that few would return from a “meeting with the Great White Bear” (Norman Davies, Trail of Hope).

Armed Russians with bayonets pointed at us

Genowefa Rataj

“At around 4 a.m. there came another knock on the door, and this time there was an armed Russian and three local Byelorussians – not friends of ours. They searched for arms everywhere in the cupboards, and then they gave us 45 minutes to pack everything. Mother started packing everything, but her nerves were giving out, so Auntie helped her….. My youngest brother was 18 months old, and there were 6 of us children altogether. We gathered what we could and loaded it on the sleigh – 45 minutes is not a lot of time to pack very much. Auntie helped Mother pack what they could. They took us first to the school, which was an assembly point where all the wagons convened. And then they took us to the train in Drohiczyn.” *

Cattle cars that still stank of their previous inhabitants

Maria Juralewicz

“We have to say that we were in cattle cars on the train – there were wooden bunks on two sides, you could fit 8 people on the top and 8 on the bottom, and in the centre there was a stove, with a stovepipe that went out the roof, and we burned coal or wood in that stove, and that’s were we could cook. As for physiological needs, well everyone is already aware that there was a hole cut in the floor, and someone would hang a blanket around it for privacy. And that is how we travelled a very long time, I believe it was about 3 weeks…..And I also remember that we got to the place where the rail line was coming to an end. And we had to go through the snow – they brought some sleighs there for us, and they brought us to these houses, built of logs. They assigned us to a room, but as there were 5 of us, they considered that this was too few, so they added a single man to our room, because there had to be 6 people to a room”.*

Soviet Propaganda and cruelty

“Once, the train was stopped, it was a very sunny day and they let us out. We were delighted by the feel of fresh air. I noticed they were filming us, it was for a propaganda film to show how delighted the Poles are at being taken to Russia, everyone was laughing, kissing and greeting each other, how could they not feel joy at a few minutes in fresh air? But it was planned to show how joyful we were to be sent to the depths of Russia.”

“We were really terribly tired and at one train stop I said that I would get some wood for this stove, I jumped out and thought such a good piece of wood, I’ll take it and felt paws on me ‘on behalf of the Soviet authorities you are arrested’ ‘for what?’ I asked. ‘For the theft of public good’…..thieves are shot immediately‘.. I didn’t realise it was a railway sleeper. The train started to move.,.and a boy jumped out saying to the soldiers, ‘thank you for finding this idiot… we can’t cope with her anymore, go’ and he pulled me back into the wagon.” *

Hymns and prayers

“We were loaded into cattle cars & when we were crossing the border we all sang religious hymns – “Nie Rzucim Ziemi” (We won’t forsake the land) was one of the songs – the doors were locked, and then opened only from time to time – ….we were on the train for a long time and we reached a place near Archangelsk.” (Władysław Rataj)

The numbers

9 – 10 February 1940: Families of settlers (osadnicy), policemen and forestry rangers (leśniczy), civil servants and government officials were deported. Wives, children, mothers and fathers were deported alongside them, whoever happened to be at home on that night. At least 220,000 people – 110 trains each carrying 2,000, deported to camps in Archangelsk, Sverdlovsk, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Irkutsk.*

12 -13 April 1940: Most of the deportees were the families of officers and ex-officers, many of whom had already disappeared without trace and were murdered in the Katyń massacres. This category also included some families of Polish military settlers (osadnicy), small farmers, policemen, forest rangers, civil servants, government officials already imprisoned in the Soviet Union and occupied Poland. A third category included families of those in hiding or abroad and families of landowners, soldiers, tradesmen, farmers and the families of previously-arrested intellectuals. At least 320,000 people in total, 160 trains each carrying 2,000 deported to camps in Kazakhstan, Sverdlovsk, Altai Kraj, Akciubinsk, Kustanaj, Petropawlosk, Semipalatinsk.*

28-29 June 1940: These were principally refugees from German-occupied Poland who had not accepted Soviet passports, intellectuals, professionals and “those likely to prove difficult to convert to communism”. In total at least 250,000 people deported to camps in Novosibirsk, Bashkirska, Maryjska, Krasnoyarski Kraj, about 10% to northern Ural, Rep. Komi.*

13-22 June 1941 deportees were Polish citizens from the Baltic States and those previously missed. At least 200,o00 scattered widely throughout the USSR.

*figures from Kresy Family Polish WWII History Group and testimonies from the Kresy Siberia Virtual Museum

A forgotten story?

This massive plan had been drawn up and signed by Colonel Serov, Deputy Commissar for Security in Soviet Russia in 1939 after the Soviets had invaded the Eastern areas of Poland (up to the border with German-occupied Poland) to remove “socially dangerous and anti-Soviet elements“. The deportees were to be ‘finished off’ in prisons, forced labour camps and places of enforced settlements in the northern parts of European Russia and Central Asia where conditions would ensure their liquidation.

“..The deportee was a non-person, a slave of the Soviet penal system, and a status at once emphasised upon arrival at prison, labor camp, or penal colony: – ‘here you will live and here you will die’; niechevo, you will get used to it; and the notorious ‘who does not work, does not eat’. …” (Michael Hope: Polish deportees in the Soviet Union. Origins of Post-War Settlement in Great Britain, London 2000). Only prisoners who worked received food rations, so those with several children or elderly parents to support had the worst conditions. Able bodied men and women worked up to 14 hours a day, felling wood, in mines, on farms with nothing but a bowl of soup and piece of bread to eat. Deaths from starvation were many.

These Soviet war crimes were not mentioned in the Nuremberg war trials and are often forgotten about with few scholarly works on the subject. “The cultural representations of World War II have been dominated by narratives of suffering, victimisation, displacement, and death, as much in Poland as elsewhere. Frequently forgotten are the stories of hope and survival of thousands of Poles who escaped the terror of war and found safe haven in distant, and often ‘exotic’, lands such as Persia, India, Africa, and Mexico.” (Exilic Childhood in Very Foreign Lands: Memoirs of Polish Refugees in World War II Ewa Stańczyk Journal of War & Cultural Studies, Volume 11 2018 – Issue 2)

Whilst the actual numbers are not known and estimates based on Russian records recently released vary vastly from 300,000 to nearly 2 million people, of which at least one third died, hopefully with time more people will study this crime. Only by listening to the voices of those who survived can we ensure this is remembered. Listen to this podcast The Polish Odyssey and share on this 80th anniversary of remembrance.

You may wish to read other posts on this subject that we should share widely so that with increased interest in WWII history, this becomes a known truth:

From the Katyń massacre to Monte Cassino – one boy’s tragic loss

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2

[…] the middle of the night, the family were arrested and, together with thousands of others, taken by cattle train into Russia as slave labour. Two of Felicja’s sons were taken by the Russians and were amongst the mass […]