These portraits are of Polish citizens from Pomorze Gdańskie (Gdansk Pomerania), forcibly conscripted to fight in the German Army during the Second World War. The course of the war was quite distinct here, largely due to the unique geopolitical situation following the Versailles Treaty (1919), with the city of Gdańsk remaining a semi-independent city with a large German population. Their fate, shared by citizens of the Second Polish Republic in other regions, is tackled in an exhibition called “Nasi Chłopcy” (Our Boys) which opened earlier this year in Gdańsk, revealing a difficult and hidden history.

I visited the exhibition over the summer and applaud the organisers for tackling the subject. Although it was presented in Polish and English, I imagine it was hard to follow for those not knowing Polish history before and after the war. It also left me with more questions than answers. These are the key points that I gleaned — some of which I pieced together myself.

Memory

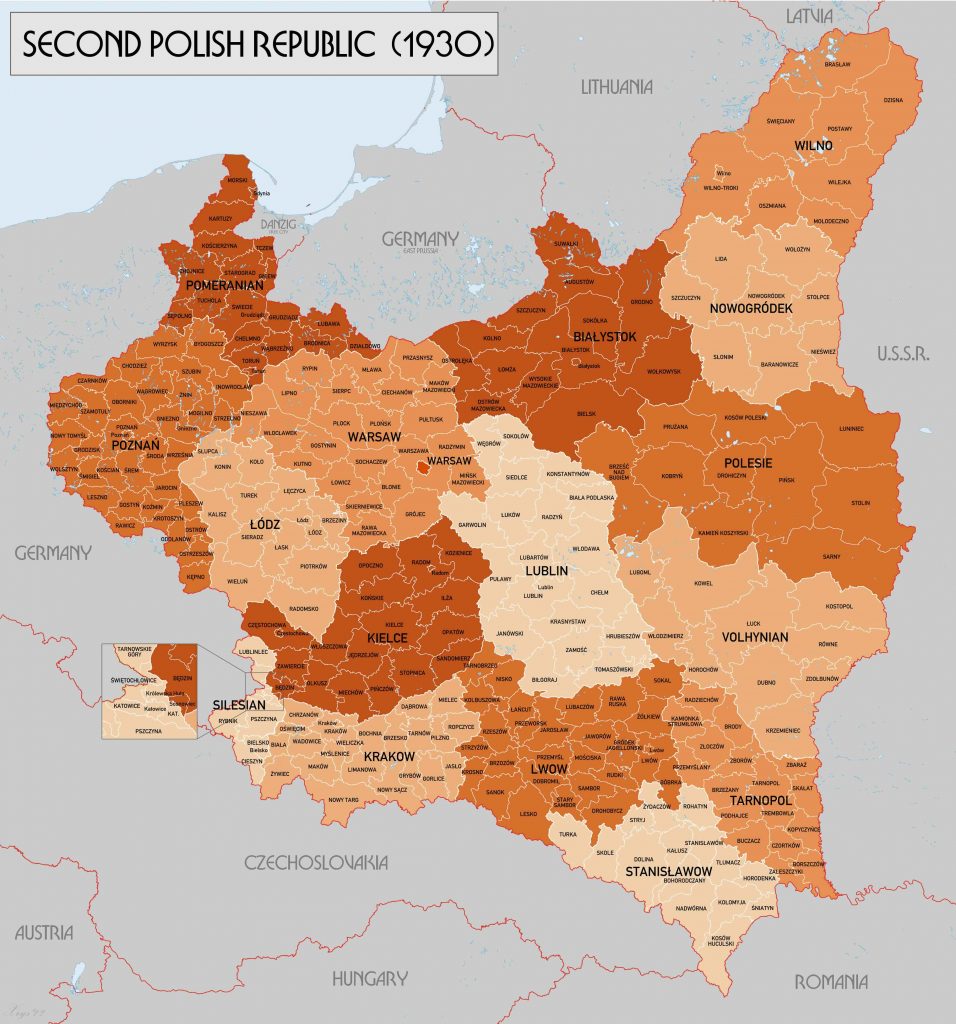

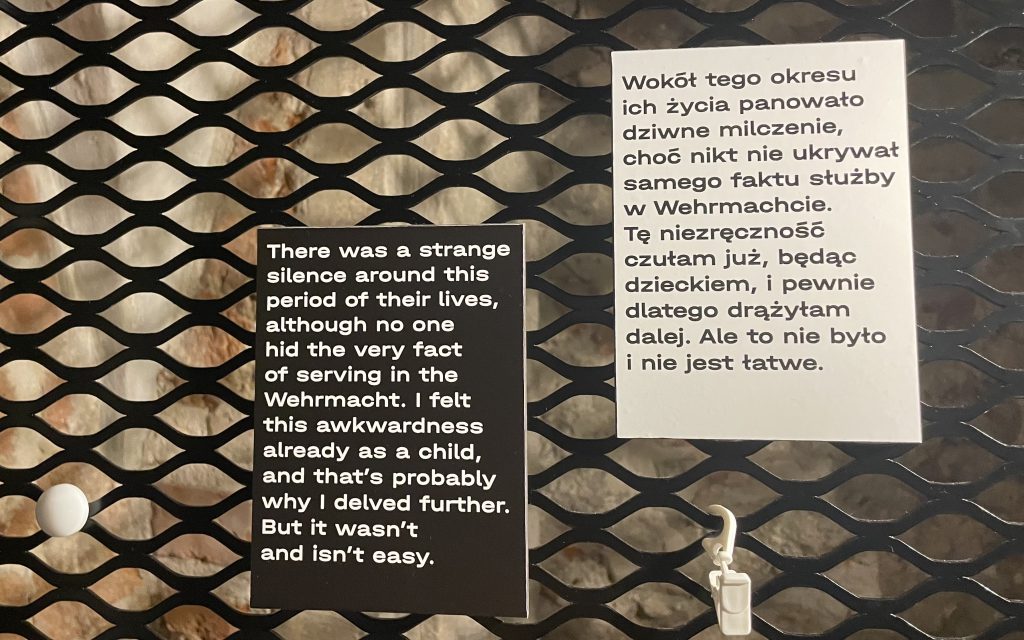

Growing up in Polish political refugee communities, I remember men who had served in the Wehrmacht (German Army) before joining the Polish Armed Forces and know their families. Like many displaced by war—through Soviet deportation, forced labor camps —they rarely spoke of that time. It is estimated that up to 400,000–500,000 men living in areas of the Second Polish Republic (1918-1939) were conscripted. They were mainly from Silesia, Pomerania, and Greater Poland.

Annexation

Pomorze Gdańskie was annexed by the Germans as early as 8 October 1939 into the Third Reich which changed the status of citizens. Remaining areas of Poland were ruled by the Generalgouvernement (General Government for occupied Polish territories). Only 25 years earlier, during the First World War, Poles had been forced to fight each other in the armies of Germany, Russia and Austria, who had partitioned Poland in the previous century. We should remember that identity was more flexible and people not only spoke Polish but often the language of the previous partitioning power, in this case German plus local dialects such as Kashubian which reflected the centuries old influence of Germany in the north of Poland.

Terror

Extermination or repatriation of ethnic Poles began as soon as September 1939. Anyone who was likely to threaten Nazi Germany was persecuted. Socially active Poles, teachers, businessmen, and priests were arrested. Many were murdered or sent to concentration camps. In the first three months of the war 30,000 – 40,000 Polish citizens from Pomorze Gdańskie were murdered. Of the 110,000 people passing through Stutthof camp east of Gdańsk, up to 1945, about half were pre-war Polish citizens, largely from this region.

Once intellectuals were eliminated, those judged by the authorities as having no German links whatsoever, were removed from the new lands of the Third Reich and forcibly resettled into the General Gubernatorial ruled parts of Poland. For example, the Germans expelled 800 Jewish Poles from near Kalisz, Pomerania in early 1940 to an eastern town of 2000 inhabitants, and the following year a number of Poles.

Deutsche Volksliste

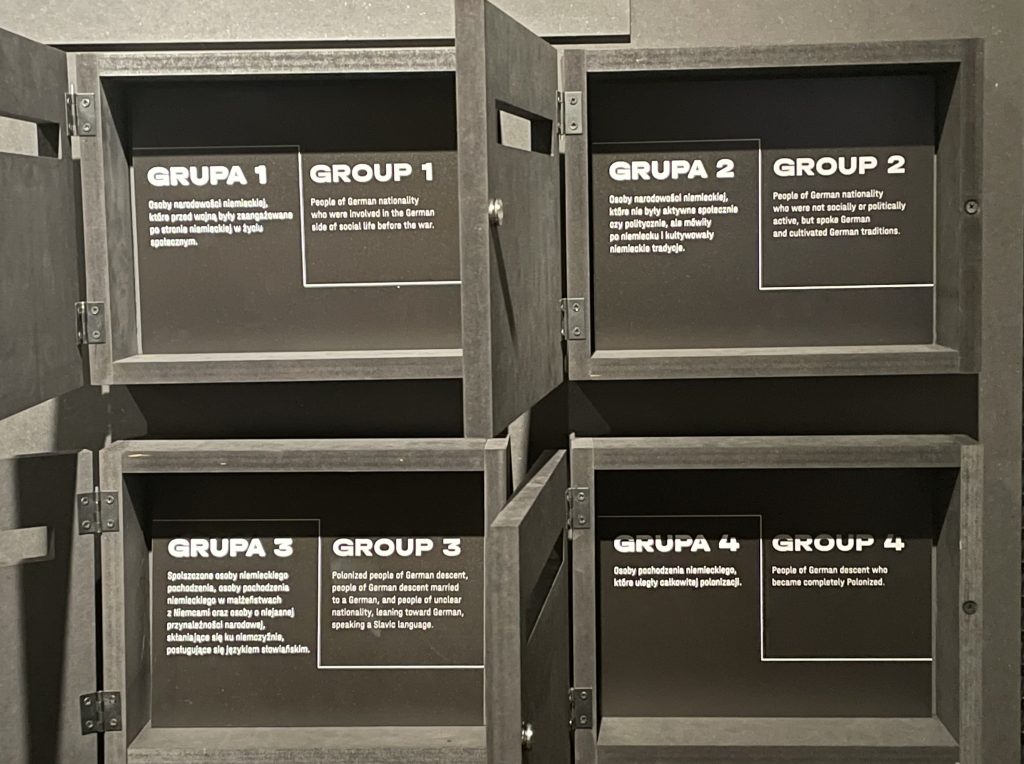

Very few people know about the Deutsche Volksliste (German People’s List) specifically intended for Poles in areas of the country annexed by Germany. After ethnic Poles had been eliminated or resettled, the remaining population was split into the following types according to Aryan background and able men were forcibly conscripted –

- Group 1 – People of German nationality who were involved in the German side of social life before the war.

- Group 2 – People of German nationality who were not socially or politically active, but spoke German and cultivated German traditions.

- Group 3 – Polonized people of German descent, people of German descent married to a German and people of unclear nationality, leaning towards German, speaking a Slavic language.

- Group 4 – People of German descent who became completely Polonised.

You were assigned a group on your documentation and there was no other way to survive for those remaining. It is important to note that volunteer enlistment in the German army was a marginal phenomenon in Gdansk Pomerania.

Death, Escape and repercussions

There is evidence that some conscripted soldiers also worked for the Polish underground giving information on troop movements or escaped when they had the chance. A quarter of conscripts died, mainly fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front. It is estimated that out of 176 conscripted men from one village Borowy Młyn with a population of around 1000 – 40 (23%) were killed, 53 (30%) managed to join the Polish Armed Forces in the West, leaving 83 men (47%) who presumably came home.

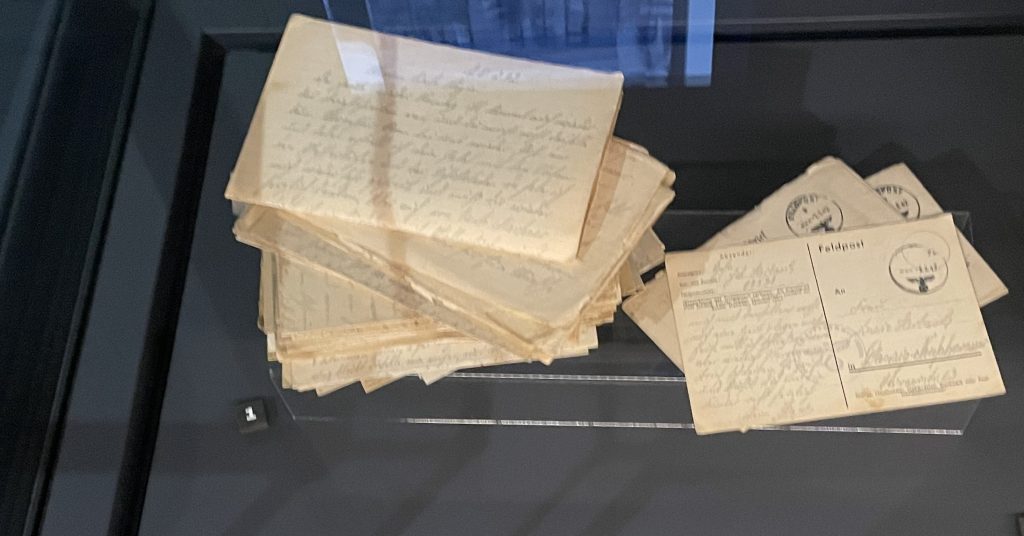

Some tried to flee during soldiers leave, to join the partisans like Edmund Tyborski, with his brother-in-law Bronislaw Marchlewicz. A traitor notified the German authorities of their dugout. Bronisław was killed on the spot. Edmund’s whole family was deported to the Potulice concentration camp and he was sentenced to death, guillotined in Cologne in 1943. Writing to family before his death, Edmund said “Księdza dostałem co mnie wysłuchał po Polsku spowiedzi i jeden ksiądz był przy mnie do ostatniej chwili – I got a priest who heard my confession in Polish and a priest was with me to the last moment“. Terror also reached those who might have thought they were safe, like German born Michał Szuca who was executed at Stutthof for working for Polish institutions.

Joining the Allies

Thousands of Polish men previously drafted into the Wehrmacht, served in France in 1944. After the Normandy landings, Allied troops quickly realised that these captured soldiers, often well trained, could be utilised. The Allies based their decision to accept these soldiers on the Hague Convention of 1907 which recognised that any oath sworn under duress to an occupying power was invalid (in this case Poland and the Free City of Gdansk). These soldiers therefore retained their original identity.

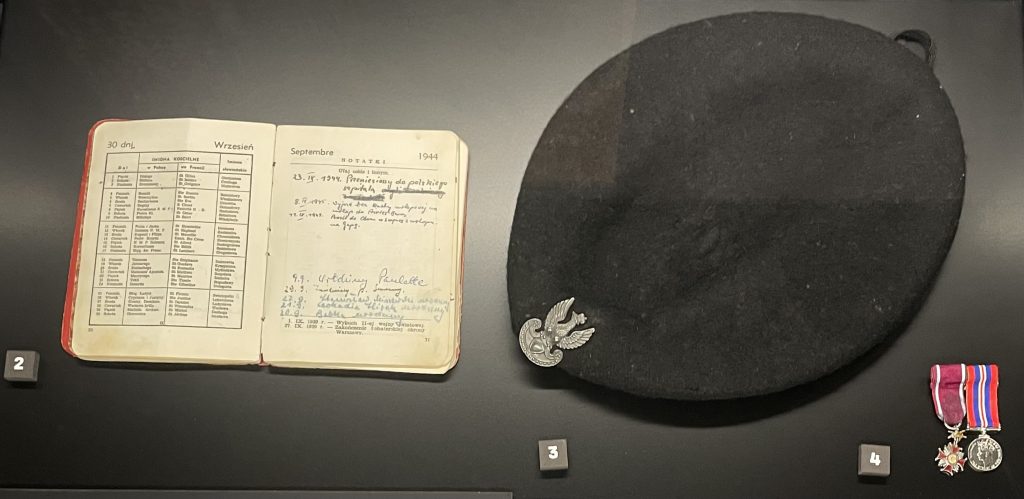

Polish ID cards, often kept by soldiers and hidden from German commanders helped to confirm Polish identity. The II Polish Corps grew by a significant amount – 25,000 joining as former Prisoners of War, escaped soldiers and released or escaped forced labourers so that by the beginning of 1945 it numbered 75,000 in total. Soldiers such as Czesław Knopp served in the 2nd Armoured Brigade of the II Polish Corps after leaving the German army.

A complex case of identity

As the exhibition has caused so much political controversy in Poland I considered whether to write this article for some time. The title “Nasi Chłopcy” – Our Boys, in particular, taken from a name used for Luxembourg conscripted soldiers, caused a lot of outrage.

Knowing many Polish families surnames of German origin who have worked tirelessly within our communities, I never considered this a controversial topic. A particular goal of the museum’s spokesperson Andrzej Giszewski is to highlight the “tragic lack of choice” faced by men entered on the Nazi Volksliste and drafted under threat of reprisals against their families. The words of Cezary Obracht-Prondzyński, a history professor at the University of Gdańsk, for me, strike the right chord. His view is that the controversy in Poland exposes deep differences in how Poland’s borderland and central regions perceive identity. Identity as we know, often shifts across generations and becomes especially complicated in times of war. Acknowledging the reality of forced conscription does not diminish the atrocities committed in Poland by Nazi Germany. Though the exhibition is modest in size, it is certainly worth visiting. I hope it marks the beginning of deeper exploration into the complex histories that have shaped so many families from Gdańsk Pomerania and other regions.

The exhibition at Gdańsk Town Hall museum on Ul. Długa 46/47 is on until 10 May 2026

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2