It’s a bit like emigrating yourself, as this new museum is placed right on the water’s edge in the renovated Dworzec Morski (Maritime Station), one of the most imposing buildings of Gdańsk during the II Republic, then left to decay after World War II.

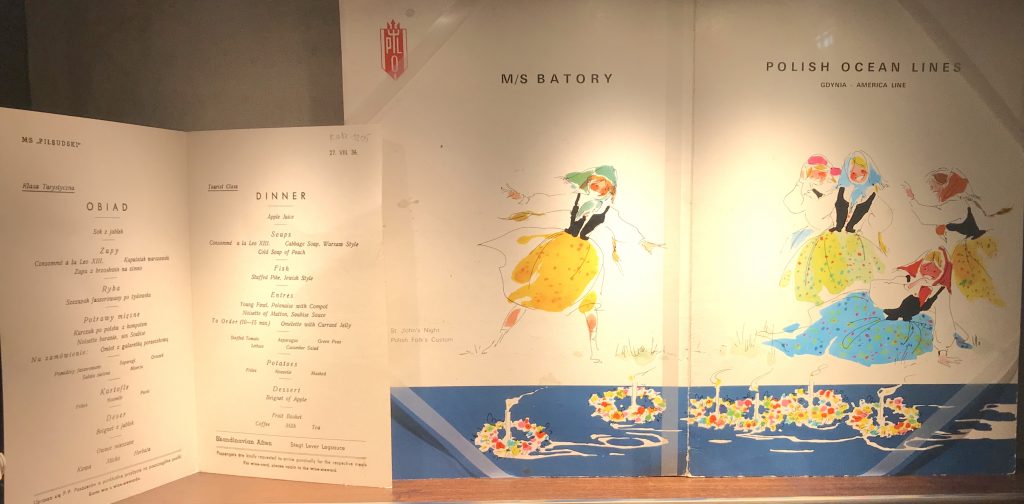

There is sense, however, in the museum being set in this building, as the Marine Station was the central hub of prewar passenger traffic and emigration. It was one of the most modern buildings of its kind in Western Europe and legendary Polish ocean liners of the interwar years– such as M.S. Batory – were moored here.

How to get there?

Here lies the problem. It’s kind of in the middle of nowhere. From the railway station (Gdynia Głòwna) your best bet is bus no 133 or apparently a 25 min walk, though part of this is a no man’s land with views of nothing better than heaps of coal and port detritus along the way. Still it’s worth it when you get there, as the building now renovated is certainly imposing.

What is there to see?

The great entrance hall is dominated by a relief of Piłsudski, Poland’s Commander-in-Chief when the station was being designed, and Ignacy Mościcki the President of Poland when it was completed in 1933. The main exhibits start upstairs and it is a great subject after all, as millions have left Poland in various ways, by choice or not, since the 18th century.

It starts with a film about Polish soldiers in Napoleon’s army singing “Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła”, composed by Józef Wybicki, which finally became the national anthem over 120 years later. The greats of Poland’s literary and cultural life are featured next, such as Mickiewicz, Chopin and Słowacki in the Great Emigration of 1830s.

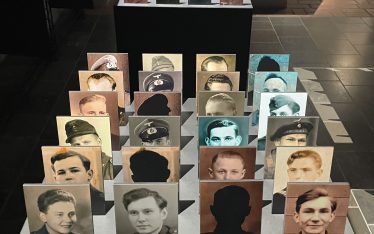

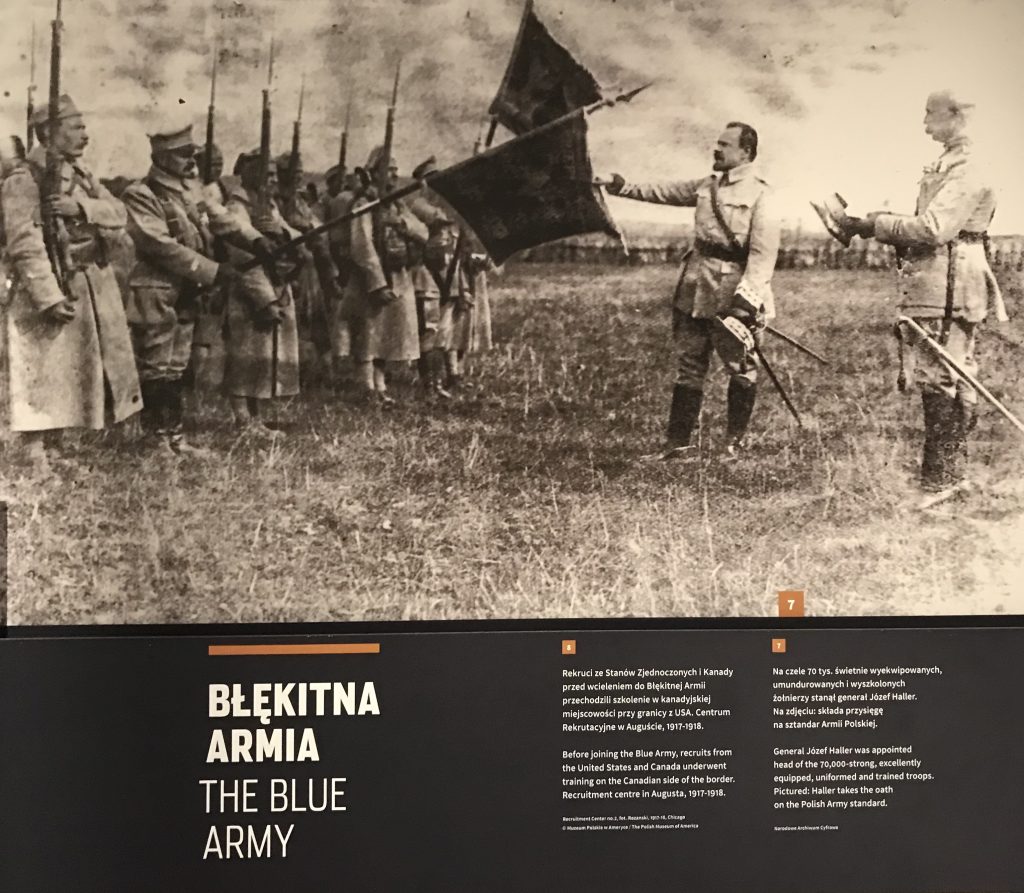

General Haller’s Blue Army during World War I gets a mention, made up of recruits from Canada and America, all fighting for Poland’s freedom. These recruits were from the families of nearly 2 million Poles who sailed to America for a better life in the 19th century. Here, individual stories tell the tale of what they left behind, the ships, the journey and arrival at Ellis Island as well as those swindled of their money or girls duped into slavery instead of the promised jobs in rich households. Tragically, not unlike today’s problems.

Emigration or forced deportation?

Sadly, although the displacement of nearly three million people into forced German labour during the war is covered, as is the repatriation of 1.2 million from the Eastern Borderlands, I’d say the Russian deportations to Siberia are lacking somewhat, given they started in the 19th century following every Uprising against the Russians, plus up to one million deported in 1940, as we well know. If I didn’t know the story I might have missed it. There’s a railway carriage showing films of people (like my Mum and Grandma) being repatriated from Poland’s former eastern lands to within Poland’s new borders after World War II but it gives little background.

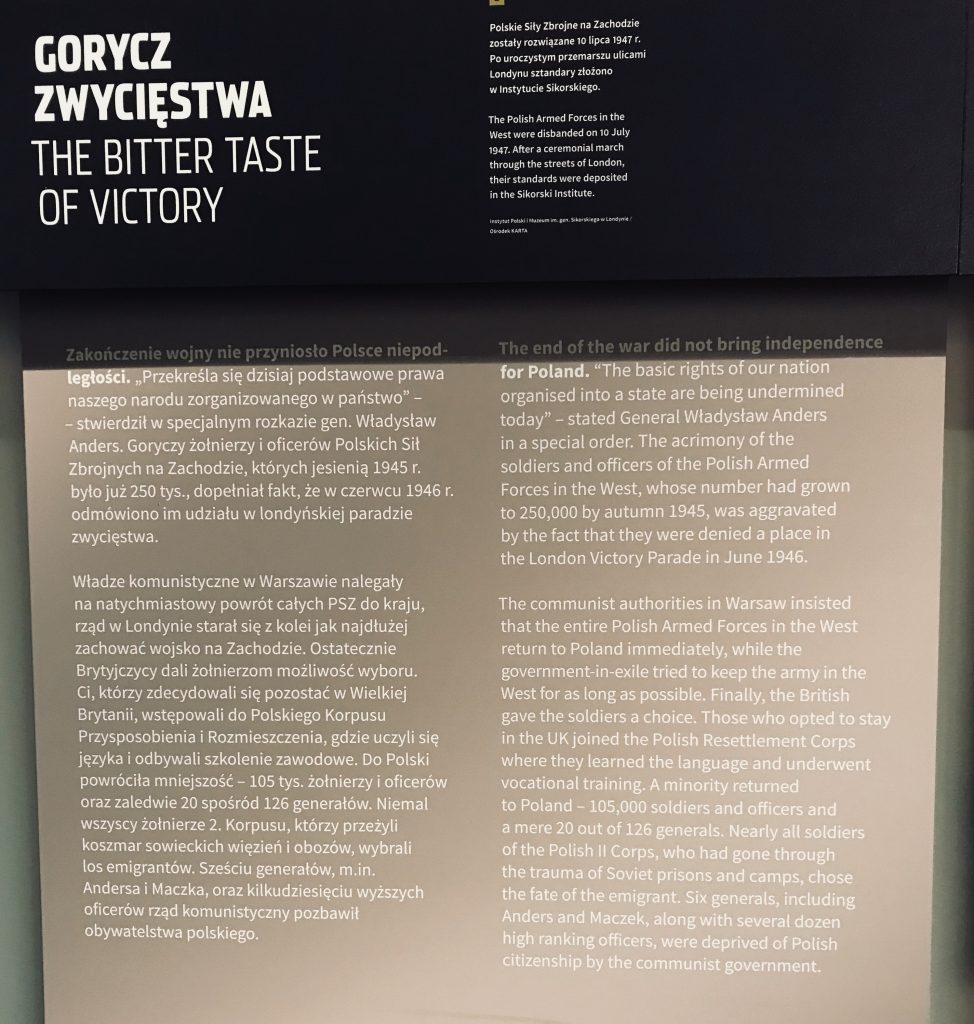

There’s also a propaganda film of soldiers who fought at Monte Cassino being greeted as heroes after 1945, yet we know the truth was vastly different and this is not mentioned, nor even how the II Polish Corps was formed from those who survived the deportations. It may be there somewhere, but it wasn’t evident to me.

Whilst emigration would suggest a voluntary element, given the museum’s directors have decided to include the vast movements of Poles during World War II, I think they should decide how better to work this into the overall story to make it comprehendable. I also didn’t see much mention of Polish Jews.

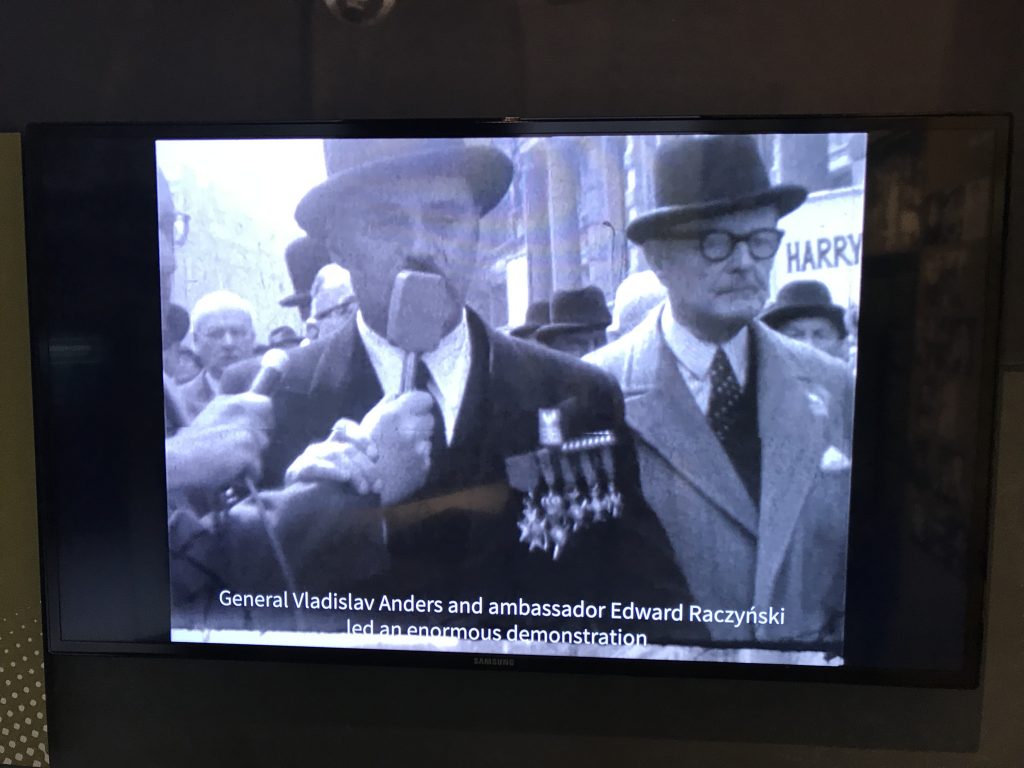

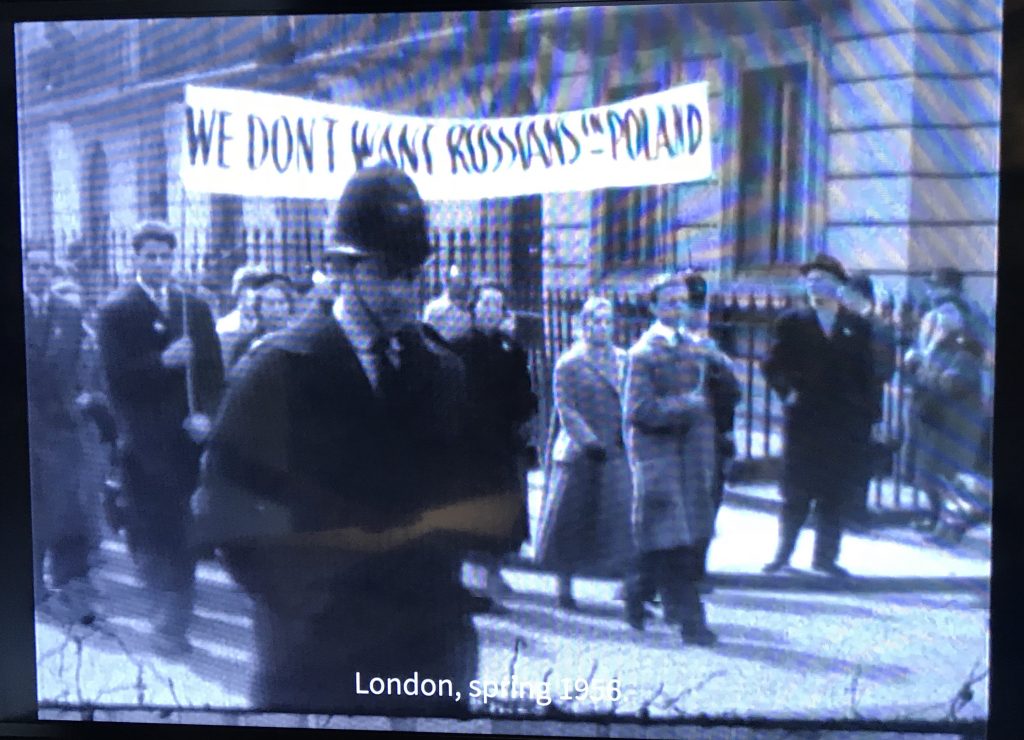

A welcome surprise then, was the exhibit about Polish London. All the Presidents of the Government in Exile are featured, the rich cultural life and emigre publications, as well as the great march in London in 1956 of 20,000 Poles and East Europeans protesting at the invitation of Khrushchev to the U.K. There was even a photo of the Bal Emigracji. I feel someone from London had a role in helping to curate this part of the exhibition.

Would I go again?

On reflection I’m not sure I would. I know most of the stories, though descendants of those who emigrated especially to The American continents would find it interesting and all the exhibits are accessible being in English as well as Polish. At the end of the exhibition you can also search the website My Ancestry records for free.

But as it’s attractive to visitors from beyond Poland, they need to improve their signposting within Gdynia. It’s rather non-existent like the days of PRL (Polish People’s Republic). Even the Tourist Info Office wasn’t signposted.

Thankfully after our visit, there was a bus waiting (no.133) which took us straight to the train station, but to my son’s dissapointment it wasn’t an electric one, of which there are many in Gdansk.

Unless you’re in Gdynia to visit “Dar Pomorza”(tall ship used for training) or the destroyer “Błyskawica”, both quite a distance from the museum, it’s quite a treck to get here.

Visiting this museum is like travelling to the ends of the earth for an exhibition that is still in development, but with some improvements it will be worth visiting. You do get that sense of displacement from the exhibits and there are a lot of interactive displays but I think for the moment I’d recommend sticking to Gdańsk and the WWII museum as there is also the Solidarity Museum to visit.

If you found this article interesting you might like to read:

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2

1.Tracing Family History pre-WW2 2. Tracing Family History WW2

2. Tracing Family History WW2